ES: TERCERA PARTE: ¿QUÉ PASA EN CUBA? UNA MIRADA ANÁRQUICA DE LAS PROTESTAS DEL 11-J.

-Interview with comrade Gustavo Rodriguez (Third of three parts)

AI: To what extent was the 1959 revolution willing to destroy the system of domination and its protagonists determined to promote a Social Revolution?

First of all, it is necessary to examine thoroughly who were the forces in conflict in 1959; what were the motivations and; above all, the ideological limitations of those involved. Of course, this is an exercise fraught with difficulties for those who continue to be fascinated by the official mythology1 and; equally difficult for those who -from different points of view, even dissidents- cling to the supposed tendencies raised by certain protagonists (Camilo Cienfuegos, Hubert Matos, Ernesto “Che” Guevara, Pastorita Núñez, for example), as if trying to decipher (at a distance of six decades) what would have been the attitude of this or that character in a specific situation or whether or not he or she was right at a given time and what would have been his or her action if he or she had greater political weight in the process. In that tenor, the legends of Camilo “anarchist”; Matos “socialist”; Che Guevara “Trotskyist” and Pastorita “feminist” arose. All dilettante speculations that in no way help to understand what those figures hypothetically opposed to revolutionary autocracy and bureaucratization represented. Unfortunately, these digressions do not manage to escape from the legends that must be demolished. Neither Cienfuegos was “anarchist” nor Matos “socialist” nor Che “Trotskyist” and, Pastorita, much less “feminist”. By the way, the latter came from the old nucleus of Fidel Castro’s nationalist militancy2 ; as did Huber Matos, Ñico López, Haydée Santamaría, among other members of the “Orthodox Youth” of the Cuban People’s Party (Orthodox)3 who would found the 26th of July Revolutionary Movement (MR-26-7).

The opposition to the Batista dictatorship was made up of a coalition of traditional nationalist (anti-imperialist) parties4 and the so-called “revolutionary movements” which -from diverse and equally nationalist perspectives- were articulated in the course of the struggle. Among the traditional parties, the following stood out: the Cuban Revolutionary Party (Authentic), which emerged after the nationalist revolution of 1933; the Cuban Orthodox People’s Party, -established in 1947 by Eduardo Chibás, after his break with the “authentic” ones-; the Cuban Revolutionary Nationalist Party (Authentic), which was formed in 1947 by Eduardo Chibás, after his break with the “authentic” ones; the Revolutionary Nationalist Party (PNR) of José Pardo Llada (co-founder of the Orthodox Party) and; the Free People’s Party, instituted by Márquez Sterling and a group of assailants of the Moncada barracks who had broken with Castro and precociously warned: “We come from armed struggle, exile and clandestinity. We have shed blood […] and we invite you to break the hateful conspiracy of silence and fear. Against Batista. Against the Dictatorship. Against the useless blood that serves as a pedestal for new pernicious dictators “5 . Among the “revolutionary movements”, the following stood out: the July 26th Revolutionary Movement (MR-26-J) led by Fidel Castro; the Revolutionary Directorate (DR), created by José Antonio Echeverría – assassinated during the ill-fated assault on the Palace – and led by Faure Chaumón; the Federation of University Students (FEU) and the Radical Liberation Movement, founded by Amalio Fiallo and several “moncadistas” who also distanced themselves from Castro’s dictatorship.

It should be noted that nationalism was the hegemonic ideology of ALL the political opposition (electoral and/or revolutionary) to the Batista dictatorship; displaying very dissimilar nuances that oscillate between bourgeois patriotism and national socialism6 . This is evidenced by such despicable slogans as “Cuba for the Cubans”, inherited from the failed Revolution of 1933, and the xenophobic laws of the ultranationalist mandate of Grau-Guiteras. Nor can it be forgotten -to have a clearer vision of the plot- that Fidel, in his university days, was accompanied by Mussolini’s “The Doctrine of Fascism” and Sorel’s “Reflections on Violence”, books that he always carried under his arm. The first time he traveled outside Cuba (1948), he was sponsored by General Juan Domingo Perón, to visit Caracas, Panama City and Bogota, as a delegate to the Inter-American Conference of Students that was held in the Colombian capital in opposition to the IX Pan-American Conference that would give rise to the Organization of American States (OAS), actively participating in the so-called “Bogotazo “7 . However, it is a proven fact that the Cuban Revolution was a bourgeois democratic revolution, whose objective was “the full restitution of the 1940 Constitution”. The tropical Bolsheviks maintained the same purpose, demanding then “clean and democratic elections “8 ; while the anarcho-syndicalists invited to “return to the country the subjugated freedom “9 , taking for granted that before March 10, 1952 it was fully enjoyed.

The middle class and the upper echelons of the oligarchy were the human, economic and ideological quarry of the Revolution; being the “working class” -with few exceptions- the great absentee10 . Likewise, it has been proven that they never set out to destroy the capitalist system (as demonstrated by the establishment of State capitalism since 1961) and, much less, to promote a Social Revolution. In fact, not even the remnants of anarcho-syndicalism, which had joined the armed struggle against Batista, promoted such an outcome. The whole discourse around the alleged “libertarian vocation” of the Cuban Revolution is framed in mythology. Unfortunately, some “comrades” still echo the myth, masking the most vulgar distortions.

AI: What forces did Cuban anarchists face from the first days of the Revolution?

In 1959 there was no “anarchist movement” but rather an anti-authoritarian tension, as I mentioned earlier. That tension was embodied in the Libertarian Association of Cuba which, according to the minutes of the II Libertarian Congress, in February 1948 registered 153 delegates throughout the archipelago. By the end of the 1950s, the decline was considerable. Revolutionary nationalism and reformist syndicalism had wreaked havoc in anarcho-syndicalist ranks. However, the comrades who survived all these onslaughts, at the triumph of the Castro revolution, had to face multiple adverse forces. Almost all of them known enemies and some yet to be known. In the first place, they had to face the bourgeoisie. Particularly, the sectors that had dressed in olive green and were “revolutionary government” but -as was to be expected-, were opposed to the radical transformations. Faced with the eventuality of workers’ control, what was at stake was not only the ownership of the means of production but the probability of preserving their privileges, now as “specialists” and “technocrats”, in positions that would allow them to have decision-making power. Everyone knows the happiness experienced by the Creole bourgeoisie when they realized that the most radical measures of the Revolution were limited to the nationalization of the means of production; assuring the continuity of domination through State capitalism which left intact the scaffolding of subjection: leader-producer; guide-followers; rulers-governed; guardians-supervised. Of course, there were also segments of that expropriated bourgeoisie that felt betrayed and unleashed a bloody struggle to regain their lost property and privileges. Naturally, the majority of the middle class maintained strong ties with the new ruling class with which they shared customs and culture, which facilitated their automatic passage into the new building of domination through “integration” (a very fashionable word in those years). Thus, they recovered their role as a ruling class, assuming their place in the new administrative elite, not only in the production process but in all social orders. Thus, they massively joined the party and occupied all the political leadership positions of the new state apparatus, glorifying the speeches of the dictator and “the successful leadership of a single man”. They went so far as to confront the weak attempts at workers’ management and the timid proposals to put an end to wage labor through the creation of workers’ councils (Trotskyists) and collectivities (anarcho-syndicalists); denouncing them as “fifth columnists”, “demagogues” and “anarchists”. Castro himself, in one of his speeches, accused Manolo Fernández, his Minister of Labor, of being “anarchist” for “promoting these demagogic experiments”, condemning him to exile.11

The second force to be confronted was the Church. From the pages of El Libertario and Solidaridad Gastronómica, the anarcho-syndicalists bluntly pointed out the imminent penetration of the clergy in the “revolutionary government”. The participation in political-administrative posts of hundreds of prominent “laymen” and militants of the University Catholic Action (graduates of the Royal College of Belen, La Salle, Maristas and the University of Villanueva); as well as the strong ties of some clergymen of the Catholic hierarchy with the ruling elite, were proof of this. Although it is true that this marriage was short-lived, coming to an end once the government declared all religious cults illegal12 -which motivated some Creole Christians to assume a violent opposition (being brutally repressed)-, very soon they had the opportunity to return to the “revolutionary abode” through the back door. To that end, they endowed the nascent Revolution with “ideology”, promoting the thesis of “Humanism” in an attempt to distance themselves from communism and the dominant capitalism. Thus, they once again occupied leading positions and even “joined” the ranks of the party, demonstrating once again “the immortality of the Holy Mother” and her capacity to always play with the bases loaded (to put it in baseball lexicon).

The third force to confront would be an old acquaintance. The eternal archenemy of anarchic praxis: the Bolsheviks. With an incredible shrewdness, the banana Leninists -just like the Church- showed their capacity to always play with the bases full and demonstrated “the immortality of the Party”. Years later, they would be even more explicit, evidencing their Machiavellian strategy under the slogan “men die, the party is immortal” (or immoral?). Indeed, during the first six months of 1959, they juggled to save their skins. At the beginning of January, the MR-26-7 took over the leadership of the Confederation of Cuban Workers, to which they added the adjective “Revolutionary” (CTC-R) and imposed a “Provisional Coordinating Committee”, led by David Salvador. By the 20th of that month, the Council of Ministers, through Law No. 22, regulated the “restoration of trade union democracy” and announced the “purification of the workers’ movement” with the expulsion of “all the splinter currents”; a clear allusion to the anarcho-syndicalist, Trotskyist-Mujalist and Stalinist-Batista PSP leaders. However, in spite of their troubled past and their proven complicity (and servility) with Batista, the Stalinists managed to avoid Fidel’s anti-communism and, above all, the firing squad. Castro had managed to carry out the (delayed) nationalist revolution, but he was late. Fascism and National Socialism were the great losers of history: the defeated of World War II. It lacked allies to confront Yankee imperialism from a “third position”, reaffirming its anti-communism. Perón had been defeated three years earlier and lived begging for asylum among related dictatorships (Paraguay, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Dominican Republic and Spain). He had no alternative but to turn to the USSR. Although the US hostilities left the Castroites no other option, the ñángaras13 had been paving the way to survive the imminent fall of Batista for some time. One of the first approaches of the Party was through erotic-affective relations with his brother Raúl, but Fidel’s visceral homophobia was the first impediment. Only eight months before Batista’s escape, the PSP founded the guerrilla detachment “Máximo Gómez” under the orders of “commander” Félix Torres González, in the mountains of Bamburanao and Gumuhaya, in the region of Yaguajay. They never fired a shot and according to testimonies, the only things they killed were pigs and cows, but when Camilo Cienfuegos passed through Las Villas, they joined Column number 2, being forced to participate in some combats. Thanks to previous contacts with Raul, the communist leader Carlos Rafael Rodriguez, in July 1958, would go up to the Sierra de San Luis to visit him and from there, he would go to the Sierra Maestra to meet with Fidel and offer him the “unconditional support of the PSP”, playing all his cards.

By November 1959, the tropical Bolsheviks managed to turn the tables and install themselves in the political leadership of the regime. From the 18th to the 21st of that month, the X National Congress of the Confederation of Cuban Workers (Revolutionary) took place, under the leadership of Fidel, who pointed out -in the face of the positioning of the different currents- that “the worst are some who pretend to defend the Revolution”; concluding that the only spirit that can prevail is “the party of us, the party of the homeland “14. At the end of the Congress, David Salvador would be ratified in the general secretariat of the CTC-R (the man proposed by Castro) but in reality Lázaro Peña, historical Stalinist leader of the CTC (the man imposed by Batista) took control again. In 1961, in spite of having been diluted in the so-called “Integrated Revolutionary Organizations” (ORI), together with other organizations; the Stalinists of the PSP continued measuring muscle and taking political control. In that same year, the XI Congress of the CTC would be held. The Confederation would change its name to Central de Trabajadores de Cuba, abandoning the old anarcho-syndicalist influences in the workers’ movement. It eliminated the affiliation to federations and imposed the affiliation to state unions, consolidating corporativism. Thus, it constituted itself as the sole representative of the Cuban workers under the command of Lázaro Peña; its main objective being “the unification of the interests of the working class”, in both trade union and political terms, around the new Party and its general secretary, Fidel Castro; which demanded the immediate “purification of its members” and the overcoming of “the errors of sectarianism”. In this context, on March 26, 1962, the United Party of the Socialist Revolution of Cuba (PURSC) was formed and Fidel Castro was unanimously elected as General Secretary of the Central Committee. Finally, on October 3, 1965, it would be constituted as the “Communist Party of Cuba” (PCC), ratifying Fidel as its “maximum leader” for life. By then, the Stalinists had not only exterminated any vestige of anarchism or anarcho-syndicalism, but eradicated all traces of its passage and influence in the so-called “workers’ movement”; changing at a stroke the history of its struggles. Thus, well-known Creole anarcho-syndicalists became, overnight, “leaders of the working class in transit to Marxism”.

AI: What’s next after the riots?

Actually, I have never been given to astral predictions. However, I can anticipate the obvious; that is, the intensification of repression, prohibitions, censorship, surveillance and convictions for “conduct contrary to socialist morality”, “disrespect”, “damage to property” and “public disorder”. Tools that the dictatorship has used throughout six decades and which it is not going to give up at this stage of the game.

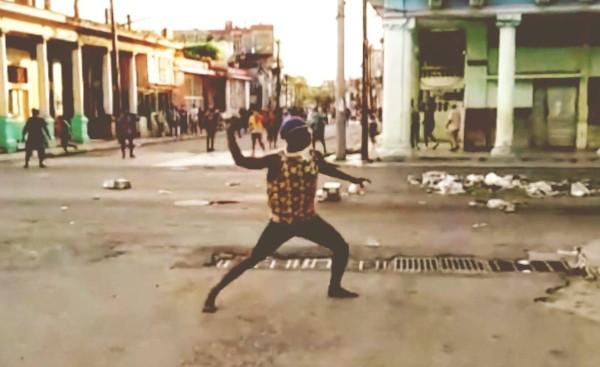

As I am informed by comrades on the island, the main cities of the country are militarized and the Black Wasps (the new repressive anti-riot corps) are making frequent rounds in the marginalized neighborhoods with the determined intention of reestablishing the fear that had ensured the tranquility of the ruling class for 62 years. To that end, they have again staged the “brigades of rapid reaction of the fighting people” to prevent any attempt of protest and; the atrocious “rallies of repudiation”, using Young Communists and Party members to attack with stones and graffiti with government slogans the houses of people the regime considers “disaffected”.

In the face of the return of repressive control -under the slogan “the streets for the revolutionaries”- and, in spite of the imposition of terror; thousands of young people remain determined to exercise the “constitutional right to demonstrate peacefully”. In this sense, they defend “the legitimacy of social activism”, with the intention of “promoting respectful debate” and “promoting the collective construction of a better country”. Proposals that are not only inscribed in the democratic discourse of “rights and duties” – alien to our anarchic objectives – but also, they are written down with candor in a letter to Santa Claus, taking for granted that the fox will renounce his nature and share, in peace and harmony, the henhouse with the hens. In this context, I consider that our place, as anarchists, is not in the streets with our faces uncovered and in broad daylight, but in the darkness of the night, as we do in all the latitudes where we have a presence. Expropriations, sabotage, the relentless attack on the structures of capital and the State, reprisals against the police, all these tasks characterize our anarchic actions and, in Cuba, it does not have to be different. The enemy is the same in any part of the planet and also represses, imprisons and shoots in all the confines.

AI: What is the situation of the prisoners of the revolt in particular and prisoners in Cuba in general?

So far there is little information on the judicial processes of the prisoners of the revolt. As I mentioned at the beginning of the interview, it is known that around 500 people are still imprisoned and that many of those who have been released are in home confinement, which in Cuba is classified as “correctional work without internment”. It is also known that summary trials have been carried out and that most of the defendants are accused of “public disorder”, “contempt” and “damage to property”; but the sentences are still unknown.

As for the situation of the prisoners in general, it is an open secret for all Cubans that the archipelago is one big prison. That has been the real social record of Castroism and not the vaunted education or health “achievements”. Between 1960 and 1980, the prison population was mostly made up of “political prisoners” (more than 10 thousand), accused of counter-revolution although, paradoxically, a very high percentage had been “revolutionaries”. Their sentences ranged from 10 to 30 years in prison. The cruelty against the so-called “critical revolutionaries” or “traitors” -former comrades of the dictator Fidel Castro in the struggle against Batista-, was of cannallesque proportions. The sentences of Commander Hubert Matos (20 years/1959-1979); Pedro Luis Boitiel (10 years/1961-1972)15 ; Mario Chanes de Armas (30 years/1961-1991)16 ; Commander Eloy Gutiérrez Menoyo (30 years, served 22/1964-1986)17 ; Gustavo Arcos Bergnes (10 and; 8 years)18 ; among others, stand out. They also showed great inclemency against the revolutionary dissidence of my generation -the so-called sons and daughters of the Revolution-, imprisoning young anarchists, Trotskyists, communists, conscientious objectors, artists and critical and gay intellectuals; sentenced for “ideological divisionism”, “counterrevolution”, “improper conduct”, “not having labor ties”, “attempting to leave the country illegally” and “refusing to perform the Compulsory Military Service”. One of the most notorious cases was that of Ariel Hidalgo, award-winning historian and pre-university professor of Marxist Philosophy; sentenced to eight years in prison for writing a critical manuscript entitled “Cuba, the Marxist State and the New Class. “19

In a note in the official newspaper Granma (propaganda organ of the PCC) in 2012, the government acknowledged having a prison population of 57 thousand people. With all the makeup of the figures, the Cuban state was then in sixth place in the international ranking of prisoners per capita. Despite the secrecy of the General Directorate of Prisons of Cuba, which considers this data, as well as the number of prisons and “rehabilitation centers” (about 300), as of mid-January 2020, some Human Rights NGOs reported 794 prisoners per 100,000 inhabitants, placing it above the United States and El Salvador. According to the same report, the number of convicts and sentenced persons annually exceeded 127,000 people; of these, 90,000 were in prison (of which 38,000 had no criminal record); the rest were in “situations of judicial and police control”. The report highlights the category of “prisoners for antisocial behavior” or “behavior contrary to socialist morality”, among which are trans women (incarcerated in prisons for men), sex workers, political dissidents and young rebels, mostly Afro-Cubans; who, in general, have not committed any crime but are considered “potential criminals” by the dictatorship and are sentenced to 1 to 4 years in prison.

Of course, Black Live Matter politicians ignore these facts and celebrate the continuation of the dictatorship. Similarly, no section of the Anarchist Black Cross has ever been interested in this situation and, I understand: “it is not politically correct to point fingers at progressive governments”. Instead, they have defended spies of the Castro dictatorship “kidnapped in the belly of the Empire”. Abolition has priorities!

AI: How can we, the insurrectional anarchists of the world, support the struggle of our kindred in Cuba?

In recent years, we informal and insurrectional anarchists have accumulated a long list of comrades in prison around the world; the party of order has undoubtedly grown stronger in every corner. However, they have not been able to control our creativity. Much less have they been able to stifle our passions or annihilate our insurrectionary desires. They put out a fire but there always remains a spark to be rekindled, there is always a loophole for insurrection. Anarchist warfare is permanent and conflict is present at any time and in any place.

Anarchists cannot prop up authoritarian regimes in the name of a hypothetical unity of “revolutionary struggles”. To link our aspirations to the perspectives of a State project, associating anarchist passions with its pretensions of domination, is to pave the way to the gallows and to cooperate with our executioners, putting the rope around our necks. We have to build our own route, stoking the rupture and the daily conflict, confronting power and Capital on a world scale; conscious that our struggle does not recognize borders. Our only commitment is with Anarchy, not with other currents, not with those who govern or pretend to govern tomorrow in the name of Revolution, Socialism or Communism. We must get in touch with those comrades who are experiencing forms of attacks on power, to act in solidarity with them, without distinction with the regimes that prevail today or those that may succeed them.

In this sense, I am reminded of the arson attack recently (3-24-2021) by a group of comrades in Malmo, Sweden, against a shopping center of the transnational IKEA, in solidarity with our comrades repressed in Belarus; considering that this capitalist company cooperates with the dictatorship of Lukashenko. And I wonder how many capitalist trusts are trading with impunity with the Cuban dictatorship and are swollen with dollars doing business with the Cuban generals, taking advantage of the benefits offered by the revolutionary paradise which does not allow independent unions and where strikes have been outlawed for six decades? do they not have their headquarters and/or branches in other latitudes where we enjoy a wide presence? Just these days, I read in related pages about an arson attack against the embassy of the dictatorship in Paris. Definitely, solidarity is much more than words and is expressed in a thousand practical ways.

AI: Would you like to add anything else?

It is inadmissible to add anything after this historiographic soap opera, to which I have also added extensive Notes. They were concise questions but they demanded extensive answers. As much as I tried to summarize, it was impossible. Answering these questions requires a much deeper analysis than what can be provided in the framework of an interview. However, any loose ends would facilitate the distortion of my words, feeding the officialist grammar. In fact, I am convinced that there will be no lack of the usual attacks and slander, because it is not that the defenders of the dictatorship are unaware of the facts, but rather that they do not want their ignominy to be divulged. They aspire to continue channeling all the rebellious and insurrectional energies around the hypothetical “unity of struggles”, to impose on us, for the umpteenth time, “Law and Order” in the name of the Social Revolution or the Workers’ State, consolidating the domination of the left of Capital. It only remains for me to thank Anarquía Info for this space and to congratulate them for the questionnaire.

Planet Earth, July 25, 2021.

1. All the historical accommodations made by the dictatorship have been “certified” since 1987 by the Institute of Cuban History. This institution was established after the merger of different political-ideological organizations that preceded it: the Department of Cuban History of the Institute of History of the Cuban Academy of Sciences (1962); the Institute of History of the Communist Movement and the Socialist Revolution (1972) and the Center for the Study of Military History.

2. “…I have been a member of only one Cuban political party, and that is the one founded by Eduardo Chibás. What morals does Mr. Batista have, however, to speak of communism if he was the Communist Party’s presidential candidate in the 1940 elections, if his electoral pamphlets were covered under the hammer and sickle, if his photos hang around with Blas Roca and Lázaro Peña, if half a dozen of his current ministers and trusted collaborators were prominent members of the Communist Party? “; Castro, Fidel, “¡Basta ya de mentiras!”, in Revista Bohemia, Year 48-No. 29, July 15, 1956, Havana, pp. 63-84 Available at https://dloc. com/UF00029010/02676 Che Guevara, years later, would describe Fidel in a letter to Ernesto Sábato, as “an aspiring deputy for a bourgeois party, as bourgeois and as respectable as the Radical party could be in Argentina; who followed in the footsteps of a disappeared leader, Eduardo Chibás, with characteristics that we could find similar to those of Yrigoyen himself […] above all, he is, above all, a man who is a bourgeois […]. above all things, he is the binder par excellence, the undisputed leader who suppresses all divergences and destroys with his disapproval. Using many times, challenging others, for money or ambition, he is always feared by his adversaries”. In: Constenla, Julia, Sábato, el hombre. La biografía definitiva, Editorial Sudamérica, Buenos Aires, 2011.

3. In June 1952, Fidel Castro ran as a candidate for the House of Representatives of the Cuban Congress, for a constituency in the province of Havana, but Batista’s coup d’état overthrew the government of Carlos Prío Socarrás and annulled the elections. The coup -recognized by the U.S. government- provoked Castro’s dismay, who would use his contacts with the Youth of the Orthodox Party to gather a group of young people for the assault on the Moncada Barracks.

4. Displaying their opportunistic mood, the Leninists of the Popular Socialist Party (PSP), celebrated the creation of what they called a “united front” against Batista -their former presidential candidate and patron- and gave their “full support” to a “government of national unity”, where they intended to participate before the debacle of the dictatorship, despite their sad past, next to Machado’s dictatorship (the “mistake of August 1933”) and his alliance with Batista (1934-1944). Just in that period, with the support of the paramilitary batons (first Machado’s and then Batista’s) they dedicated themselves to assassinate anarchists, anarcho-syndicalists and Trotskyists.

5. Manifesto to Public Opinion”, Partido del Pueblo Libre, June 30, 1958.

6. After the failed nationalist revolution of 1933 and the coming to power of the ultra-nationalist government of Grau-Guiteras (the “government of one hundred days” in 1934), fascist ideas coming from Europe began to gain strength. The Nazi-fascist ideology would become even more prominent during the presidency of Colonel Federico Laredo Brú (1936-1940), with the implementation of corporativism, the creation of the Civic-Military Institute and the imposition of Decree 55 (January 1939) and Decree 937 (May of the same year) that prohibited the entry of immigrants. Laredo Brú, would take on the task of organizing a constituent assembly for a new Magna Carta that defended without any concealment “a Cuba for the Cubans” (Constitution of 1940), flaunting his xenophobic ideals. At the end of the 1930s, he would remorselessly award the Order of Merit to Nazi ministers Joaquin von Ribbentrop and V. von Bulow Schwant. In that context, several organizations and parties of National Socialist affiliation would be created, highlighting the Nazi Party of Cuba (October 1938) and the National Fascist Party (founded that same year). At that time, the National Revolutionary Syndicalist Legion; the Student Legion of Cuba; the Cuban Falange (Spanish Falange Party of Cuba, founded in June 1936) and the Winter Campaign Fund were registered. In this sense, an infinite number of pamphlets and “organs of diffusion” were published. Nazi propaganda and anti-Semitic campaigns -for the “Cubanization” and in “defense of the native interests” against the invasion of the “human garbage”, the “merchants thrown out of the temple” and of “the Yankee-Jewish entity”, which announced a future where “we will then suffer the consequences of a new type of capitalism that does not speak our language, nor does it believe in our God, nor does it feel our God, nor does it feel the consequences of a new type of capitalism that does not speak our language, nor does it believe in our God, nor does it feel the consequences of a new type of capitalism that does not speak our language, nor believes in our God, nor feels our concerns”- came to be spread in radio programs and newspapers of wide circulation (Diario de la Marina, Diario La Discusión, the newspaper Alerta, the newspaper El Avance criollo and the magazine Sí). The Catholic Church would also play a decisive role in support of the Spanish fascists, defending the Francoist uprising from the pulpit and through teaching in Catholic schools, whose teachers were mostly Spanish nuns and priests of Francoist affiliation who had migrated to Cuba fleeing “the anarchist terror”. A large part of the Cuban and Spanish bourgeoisie residing on the island sent their children to be “trained” in those centers of religious education, which is why many of them identified themselves with this ideological side. Such would be the story of Fidel Castro Ruz, whom his father (a Galician landowner sympathetic to Franco), would enroll in 1943, at the age of 16, in the Real Colegio de Belen (a Jesuit institution, founded in 1854 by Queen Isabel II), after having completed his primary studies in La Salle (1935) and Dolores (1938). In spite of such coincidences, perhaps it was a product of causality that Fidel, in his plea (“History will absolve me”) after the ill-fated assault on the Moncada barracks, pronounced a speech very similar to the one issued by Hitler in his defense, for the failed coup d’état of November 1923 (Beer Putsch Hall): “Pronounce us guilty a thousand times, that the goddess of the eternal court of history will smile and break to pieces the decisions of the state prosecutor and the verdict of the court, for she will acquit us. ” No doubt it was also chance that motivated him to call his opponents “worms” (würmer), just as Hitler did a couple of decades earlier. Or hiring former Waffen-SS and former Nazi paracidists in 1962 (at the height of the “Missile Crisis”), as military advisors and instructors of his newly created Revolutionary Armed Forces (FAR). It was no coincidence that he was in contact with a network of Nazi arms dealers headed by Otto Ernst Remer, to whom he ordered the purchase of thousands of Belgian-made machine guns. Or, that he agreed with Franco the purchase of Pegaso buses for public transportation to replace the Yankee General Motors. Or what do you think?

7. Of course, there are those who speculate in a dilettante manner that Perón’s National Socialism was (and is) “leftist”. Of course, the need to ask what the fuck is the “left” is increasingly evident.

8. Manifesto of the National Committee of the Popular Socialist Party, June 28, 1958; signed by Juan Marinello and Blas Roca.

9. Report of the National Libertarian Conference, National Council of the Libertarian Association of Cuba, Campo Florido, April 24, 1955.

10. The resounding failure of the “general strike” of April 1958 called by the MR-26-7, is an irrefutable demonstration of the distancing of this political-military organization from the “workers’ movement”. The trade unions had been under the control of the Stalinists since August 1933 (with the assault on the CNOC in collusion with Machado). Their power was reinforced in 1939 with the gift from General Batista of the Confederation of Cuban Workers (CTC), imposing Lázaro Peña as secretary general, and their interference in the “workers’ movement” would continue until 1947. It was then that the unstoppable decline of the Popular Socialist Party (PSP) would begin, losing the leadership of most of the unions. During those years they would also lose more than half of their militancy. Later, the Trotskyists would take the baton through the Workers’ Commission of the Cuban-Authentic Revolutionary Party, reaching positions in the main trade unions under the leadership of Eusebio Mujal and, after the new military coup (March 10, 1952), they would go over to Batista. It is worth noting that the PSP (Stalinists), in its Manifesto of April 12, 1958, strongly condemned the “unilateral call” for a strike called by the MR-26-7 for April 6, 1958.

11. “One day I made a criticism -and I believe it was a well-made criticism- against that demagogue whom I called anarcho-crazy, because in reality he was nothing else, that one fine day, out of politicking, in those days when there were a series of currents, that there were people who adopted purely demagogic measures, who unthinkingly and without consulting anyone, decided on a problem such as the problem of equalizing the salaries of the construction sector in the interior with those of the capital, without taking into account the tremendous repercussion that this was going to have on agriculture and on the displacement of the labor force from agriculture to construction. And precisely, those days when the Revolution had initiated a series of works to provide employment, as one of the many means to put an end to unemployment before agriculture acquired greater development.” Speech by dictator Fidel Castro, June 30, 1963. Available at: http://www.cuba.cu/gobierno/discursos/1963/esp/f300663e.html

12. When Fidel Castro promulgated the Marxist-Leninist character of his government, numerous pastors, priests and nuns were expelled from the country, just as Franco had done with the sector of the Church he considered “opposition”. In 1963, all religious schools (Catholic, Protestant and Jewish) were nationalized, prohibiting religious education. In 1965, the Communist Party of Cuba was consolidated as the hegemonic political force, forcing the “integration” of all the currents that had intervened in the insurrectional struggle against Batista in the only political institution allowed, under the Leninist conception of the construction of socialism as the central objective. Thus, it imposed in its Statutes the priority of eradicating “religious obscurantism”, which was immediately translated as the exclusion of “believers” in all political-social activities. Such measures not only prevented their militancy in the Party but also demanded their expulsion from certain state functions (teaching, for example) and access to university studies, among others. These institutional regulations against “believers” included all “cults”, including Afro-Cuban religions, which were fought with particular viciousness (highlighting the persecution and infiltration of the Abakuá plants). It was then that they implemented the Military Units of Aid to Production; better known by its acronym UMAP (1965-1968), a euphemism that disguised the forced labor camps, where religious, lumpen proletarians and homosexuals, among others, were confined. In 1991, in the midst of a severe economic crisis, which was called “special period” -after the collapse of the Soviet Union-, the dictatorship reduced the coercion on religions and the (only) Party backed down, accepting the militancy of “believers” in its ranks. In an attempt to alleviate the crisis, they then promoted “religious reactivation”, allowing a greater presence of religions in Cuban society and “social assistance” through donations of humanitarian aid for schools, hospitals, homes for the elderly and social works; in addition to participating in social and economic development projects; displaying the historical Bolshevik opportunism.

13. A derogatory adjective used by the Abakuá ekobios to refer to the Bolsheviks – since the beginning of the 20th century – as a result of the influences and closeness with Creole anarchism.

14. Speech given by the dictator at the opening of the X Congress of the CTC, November 18, 1959. Available at: http://www.fidelcastro.cu/es/discursos/discurso-en-la-apertura-del-x-congreso-de-la-ctc

15. Leader of the student movement, militant of the MR-26-7 and responsible for the clandestine radio plant of this organization. Arrested and tortured twice during the struggle against the Batista dictatorship, he was forced to go into exile in Venezuela until the triumph of the revolutionaries. In 1961, he was accused by the new regime of “conspiracy against the State” and sentenced to 10 years in prison; once imprisoned, his sentence was extended on two additional charges. He died on May 25, 1972, at the age of 41, after a prolonged hunger strike (53 days) in the prison of the Castle of the Prince in Havana.

16. Assailant of the Moncada Barracks on July 26, 1953, taken prisoner together with Fidel, with whom he shared prison in the Isla de Pinos Model Prison. Founding member of the MR-26-7 and organizer and participant of the Granma yacht expedition (together with Fidel, Raul and Ché). At the triumph of the Revolution he was imprisoned in Batista’s jails for being responsible for “action and sabotage” in the province of Havana. Once released he collaborated in the revolutionary high command. He was arrested at the end of 1960 on direct orders from Fidel and convicted on the charge of “conspiring by word of mouth” against the dictator, being sentenced to 30 years in prison.

17. Son of Dr. Carlos Gutiérrez Zabaleta, major of the Republican Popular Army during the Spanish Civil War. He was an urban guerrilla of the Revolutionary Directorate (DR) from the age of 21. He participated with his brothers in the failed assault on the Presidential Palace on March 13, 1957, where his brother Carlos was killed in combat. He was head of “action and sabotage” for the DR in the province of Havana. In November 1957, he accepted the command of the National Front (Escambray) and initiated in Banao, Las Villas province, the rural guerrilla against Batista. After Batista’s escape, his troops were the first to arrive in Havana, recognizing Fidel’s triumph. When he noticed the Stalinist turn of the Revolution at the end of 1959, he confronted Ché and Raúl and, immediately after, he tried to reorganize his guerrilla group in the Escambray, this time to overthrow Castro. In 1961 he fled to the United States and was detained in Texas for six months. By 1963, he established a base on one of the islands of the Bahamas from where he began to operate against the Cuban government, being imprisoned again by the U.S. authorities. In December 1964, he led a landing in Baracoa, Cuba; after a month of resistance in the region, he was captured by the army and condemned to death in a summary trial that lasted 30 minutes. His sentence was commuted to 30 years in prison in exchange for a televised “mea culpa”. In 1970, he received an additional 25-year sentence for “conspiring from prison”. On December 20, 1986, he was released from prison under international pressure after 22 years and deported to Spain. In mid-1995 he traveled to Havana to meet with Fidel in search of “reconciliation and a peaceful transition of the regime”; for which he was branded a traitor by the Cuban exile community. He died in Havana on October 26, 2012, after his unsuccessful attempt at “political opening”.

18. In July 1953, he participated in the assault on the Moncada Barracks together with Fidel, with whom he served his sentence on the Isle of Pines, after being seriously wounded in combat. Once released from prison, he went into exile in Mexico, where he participated in the preparations for the Granma yacht. He was number 83 on the expeditionary list but could not embark due to his precarious state of health. At the end of 1957, he returned clandestinely to Cuba and joined the struggle against Batista. After the revolutionary triumph, he was appointed Cuban ambassador in Brussels until 1966. His critical positions against the dictatorship cost him the diplomatic post, being prosecuted and sentenced to 10 years in prison, of which he served 3, after a long hunger strike that put him on the verge of death. Years later, he would be imprisoned again for attempted “illegal exit from the country” and sentenced to 8 years in prison. He served the full sentence despite his deteriorating health and being the oldest prisoner in Cuban jails. He died in Havana on August 8, 2006, at the age of 79.

19. In an Addendum to his sentence, it is ordered “as for his work, destroy it by fire.”

Source: Anarquía Info