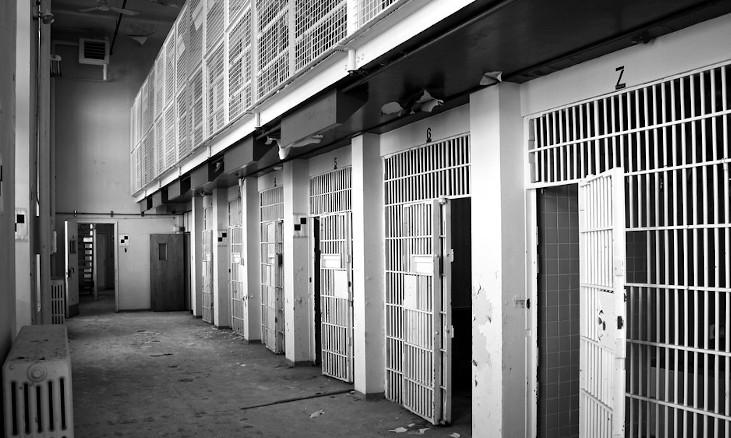

(Above) The now closed P4W (Prison for Women) in Kingston, Ontario.

Originally published at Kersplebedeb

Ann Hansen was imprisoned in 1983 for her involvement in the urban guerilla group Direct Action. She is the author of Direct Action: Memoirs of an Urban Guerilla and Taking the Rap: Women Doing Time for Society’s Crimes. She wrote the introduction for Margrit Schiller’s Remembering the Armed Struggle: My Time with the Red Army Faction. This interview was conducted in the summer of 2021.

How would you like to introduce yourself?

I am a 67 year old white cis gender female anarchist on parole for life after being convicted of a number of actions in 1984 along with some members of the urban guerrilla group, Direct Action. Since being released from prison, I have been living for almost 25 years now on a small farm that I own near Odessa just west of Kingston, Ontario. I am active with the Prison for Women (P4W) Memorial Collective which has been fighting for a Memorial Garden at the site of the now closed Prison for Women, and a Gallery where the women’s art and writing can be seen in order to give some context to their lives and deaths.We also agitate to improve prison and parole conditions as a harm reduction tactic in order to alleviate some of the suffering, but always within the context of the abolition of prisons and capitalism as the goal, the light that guides us through the darkness

I should also add that my parole conditions have a direct impact on my political activism. In 2012, my parole was suspended for allegedly not telling my parole officer about a Prisoners Justice Day (PJD) film I screened at the Kingston public library in conjunction with a lawyer who outlined our civil rights in the context of large civil disobedience actions. My parole was reinstated by the Parole Board but only after adding this new parole condition in which I must “notify” my parole officer about any political activity in which I am engaged, such as attending events, public speaking, writing, etc. Even though the word is “notify” as opposed to “approve,” they could revoke me for anything. This seems shocking to activists, but any prisoner who has been on parole knows that you can be revoked for anything, anytime. It is very common to be suspended for obscure things like “deteriorating behavior” or “having a bad attitude,” especially if you are not a politicized prisoner. Politicized prisoners usually have some community support and a radical lawyer, so parole suspensions are more likely in the public eye and thus parole officers and the Parole Board are more accountable. “Social prisoners” on the other hand are usually invisible and are less likely to have legal representation so parole officers feel less constrained in terms of suspending them for ridiculous reasons.

Whenever I hear people expressing shock at the restrictions placed on political prisoners in countries like China and Russia, I smile cynically, because conditions for prisoners and parolees are not much better in Europe and North America. I bring this up because this particular parole condition has a big impact on what I can do or say. In the Kingston public library in 2012, my decision to show a PJD film at the same event as the lawyer explaining citizen’s rights during civil disobedience actions, was interpreted by my parole officer as and as a result I was “reverting to a pattern of behavior similar to that which led to my ‘index offence.’”

It is very important to note that this condition is applied to many prisoners who are not politicized, even if it is not an actual condition of their parole. Many prisoners are warned that if they take up speaking or writing about their experiences on parole or even in prison that they will be revoked. So it is also very important that our activism be extended to cover all prisoners whether they were arrested for so-called political actions or a prisoner who committed a crime they do not consider political. I will expand on this later.

The effect from these kinds of conditions is to cause prisoners to self-censor both their words and deeds. Whenever I am engaged politically I find myself subconsciously asking myself “Is this action or article worth having my parole revoked and possibly years and years back inside?” Many people who have had their parole revoked have told me that without a good lawyer, the odds are very low that you will be released or reinstated. In my case, I was privileged to have a good radical lawyer offer his services pro bono, but even then Legal Aid still charged me $4,000.00 because I own a home. I am not complaining about the $4,000.00 Legal Aid fee because I am privileged to even “own” a home, but the point remains, that pro bono lawyers are hard to come by, and that without one, your odds of being released after your parole hearing are low.

So I constantly am weighing the worthiness of writing political articles or participating in political actions relative to my freedom. A lot of people who have never been on parole, condemn people on parole for giving up activism or not being hardcore enough, shaming them for being “sell-outs.” I challenge them to imagine risking their home, family and life just to attend a demonstration.

How would you describe your politics?

I think a person’s political views are better described through their value system than by some ideological brand, such as anarchism, communism, capitalism or socialism. Any country or individual can claim to be “communist” or anarchist but in practice, still be capitalist. If the most important value that guides either a country or individual is the accumulation of individual wealth, then whether they have a strong State or not, they are not communists or anarchists.

I would describe myself strategically as an anarchist revolutionary who believes that harm reduction tactics are valid in order to achieve our ideals. I have used the following story before to succinctly explain why I believe that fighting for improved prison and parole conditions are valid within a revolutionary context. If you were to visit someone in prison who has been in isolation for over a year, and they asked you what your activist group was doing, and you said writing pamphlets or speaking out at events about the need for revolutionary change, I would literally bet the farm, that they would either be crying inside or outright yell at you for not doing something to actually get them out of “the hole” now. Most of us, especially us white privileged folks, do not have a clue what it is like to be in a prison isolation cell or special handling unit or even just the general prison population. It is not out of line to call it “hell on earth.” Prisoners would either laugh or cry at the idea they should wait for the revolution before expecting to be “free,” or even released from isolation.

At 67, I have developed a certain level of cynicism about the revolution happening, not just in my lifetime, but perhaps anyone’s lifetime, and so it seems cruel to ask the majority of the world’s population to wait for the revolution if they want their suffering alleviated. They need food, drinking water, shelter, their land and freedom now, not on paper or in their dreams, but right now. This harm reduction philosophy originated within the drug-user communities where activists realized that the all-or-nothing “just quit” philosophy wasn’t going to work for lots of people, so why not get them clean needles and maintenance drugs such as methadone, tools and practices for minimizing risks and reducing harm?. By reducing misery and desperation in our communities, these practices also benefit people who aren’t using criminalized drugs.

In your Introduction to the new English translation of Margrit Schiller’s time in the Red Army Faction (German urban guerilla group), you trace how the exceptional conditions designed to break down political prisoners in the 1970s (23 hour lock-up, isolation, constant video surveillance, etc.) became regular features of the present-day prison system. Can you talk a bit about this? Why do you think this has happened?

Capitalism is nothing if not resilient and adaptable. Over the past 500 years, capitalism has evolved into the dominant global economic system, distinguished from other economic models by values rooted in materialism, hierarchical power structures and competition. Historically, capitalism has weathered many storms: communist revolutions in Russia, China and Cuba, not to mention various national liberation movements and sieges. Although the communist revolutions in Russia, China and Cuba were guided by communist ideals in the beginning, they quickly got stuck in the mire of greed during the “dictatorship of the proletariat” phase of the revolution. Soon these fledgling “communist” countries replaced private corporations with State-owned corporations, and replaced the powerful ruling elites of private corporations with the vanguard of the Communist Party and State bureaucrats. These State-run corporations and their communist vanguard quickly evolved into a different strain of capitalism, commonly referred to as State capitalism.

Historically, capitalism has continued to adapt to changing social conditions. So, when the State introduced isolation, sensory deprivation, intensive surveillance, drug “therapy,” and other psychological techniques to break down political prisoners, it didn’t take long for the State to replicate these techniques to breakdown any prisoner who resists in either thought or deed. Since the closure of P4W (Prison for Women), these psychological techniques of breaking down a person’s identity are very evident in the “new” federal prisons for women.

P4W was the only prison for women in Canada from 1934 to 2000. When it closed down in 2000, six new federal prisons for women were opened, allegedly to create prison conditions that were more women- and Indigenous-centered, and would provide more job skills training and education. If anything, since the closure of P4W, prison conditions have deteriorated and opportunities for job training and education have diminished, while the security apparatus has evolved and become much more sophisticated and all-pervasive. Modern repressive security conditions that were once applied to political prisoners globally in the 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s, have now become ubiquitous and used against any prisoners that resist whether they are politically enlightened or not.

For example, the segregation unit in P4W was only separated from the main range by an electrical/plumbing corridor running along behind all the cells on both sides of the range which facilitated communication between segregated and general population prisoners. All day long, as women went up and down the stairs from the general population main range to the upper tier, they would shout through the crack in a fire escape door to the women in segregation. It was very comforting to the women in seg to hear women yelling down to them all day long.

In the six regional federal prisons for women, segregation units are located in the maximum security units which are tiny separate buildings with a maximum capacity of approximately 30 women. Even within the max units, the segregation area is usually isolated on the main floor, separated by thick concrete walls from the pods so that it is difficult to even hear women screaming, let alone yelling back and forth through the doors like we did in P4W.

In P4W there was a heavy metal gate that opened and closed electronically, clanging noisily on its metal tracks each time it opened or closed. These doors opened up onto 100 cells that made up A and B range, including the segregation cells that made up the back half of B range. This clanging as the metal doors hit the metal door stop gave the women lots of warning that a guard or even tradesman was coming down the range.Other than the guards marching through the ranges doing hourly counts, there was no other means of surveillance. There wasn’t even an intercom system on the ranges, only in the newer social development addition that was constructed during a progressive period in the 70’s, when governments embraced education and job skills training in an attempt to lower the recidivism rate.

There was absolutely no audio-video surveillance like there is today in the maximum security units, where 2 round bluish eye-like cameras record everything within a 360 degree radius, on each end of a roughly 80 foot long by 30 foot wide pod. The maximum security units consist of 3 pods each and a segregation unit. Each pod is long enough for 5 cells, a bath/shower cell and a laundry/dryer unit, and wide enough for a 3 foot walking corridor in front of the cells and another 20 feet in which chairs, a TV, kitchen cabinets, a fridge and sink flank the walls.

The maximum security units alone are a prime example of how enhanced security features, originally designed to control political prisoners, are now used to target any prisoner that is resisting or not conforming to the prison regime. When Millhaven, the first super max penitentiary in Canada, was opened in 1971, followed by the “Correctional Development Center” in Quebec, the Correctional Services of Canada (CSC) incorporated a “special handling unit” (SHU) where they could isolate small groups of prisoners who had killed a cop or guard or even another prisoner, from general population for an indefiniate period of time. With the exception of the nationalist movement in Quebec, there was very little organized resistance in Canada at the time.

The CSC needed no cause to embrace any technological advancements that would enhance their capacity to surveil and control general population prisoners. So when 360 degree 24/7 audio-video surveillance became viable, the CSC incorporated these systems into all their prisons, putting a sinister spin on the motto “build it, and they will come.”

The maximum security units in the women’s prisons are by design and function special handling units, except instead of being reserved for prisoners who have killed cops, guards or other prisoners, they are used to hold any prisoner who is convicted in institutional court for anything from having a syringe in their cell to fighting. The maximum security units are also used to hold women convicted of murder for at least 2 years, most of whom have killed someone who was abusing them.1

When I was suspended in 2012, I was placed in the maximum security unit, even though I had neither been convicted in institutional court nor murdered anyone. I had been suspended for screening a Prisoners Justice Day film in the public library in conjunction with a lawyer giving a talk on an individual’s civil rights during mass civil disobedience actions. I put in a complaint immediately because clearly this was a form of punishment in and of itself, considering I had been out since around 1992, owned a small farm and was not engaged in any illegal or dangerous activity. After my parole was reinstated by the Parole Board, and about 3 months after I had filed my complaint, it was returned with an apology for the bureaucratic error of placing me in the maximum security unit.

I was definitely shocked at the level of security in this unit for a group of roughly 20 women separated into 3 pods, plus a segregation unit. There was virtually no work for the women in max. They had to stay on the pod all day except for one hour of exercise in a yard the size of a doubles tennis court, and the women in the different pods were never allowed to exercise with or have any contact with one another. When you arrive in the maximum security unit, you start off at the highest security level 4, which means that you must be handcuffed and shackled, and accompanied by a guard every time you leave the pod. If you conform and remain charge-free, your security level can drop to level 3 after a few months, at which time you can leave the pod in handcuffs without leg shackles but still with a guard in tow. Level 2 involves being escorted off the pod with a guard but without restraints, and finally at level 1 you can leave the max unit with just a pass, no guard or cuffs. It is ridiculous.

You also went to prison for urban guerilla activity, but in Canada in the 1980s and as a member of a much smaller organization (Direct Action). What were some of the similarities and differences you noticed between Schiller’s experience and your own, both in the underground and once you were imprisoned?

As you say, our group, Direct Action was much smaller than the Red Army Faction (RAF). The revolutionary movement which fostered Direct Action was also much smaller and not as advanced ideologically. We really only had 2 underground cells at any given time, whereas the RAF was one of two urban guerrilla groups supported by a significant revolutionary movement in West Germany alone, and both the June 2nd Movement and the RAF were much larger than Direct Action. There was also significant urban guerrilla activity throughout Europe during the 70’s and 80’s, with the Red Brigades in Italy, the Angry Brigade in Britain, the IRA in Ireland, and ETA, the Basque separatist group in Spain, to name just a few. This significant number of guerilla groups throughout Europe reflected the fact that the European revolutionary left had a much more sophisticated political analysis and practice, resulting in a large extra-parliamentarian left which metaphorically created a significant body of water in which the fish could swim.

Here in Canada, the FLQ had been decimated when the War Measures Act was implemented in 1970 after the kidnapping and killing of Quebec’s Minister of Immigration and Labor, Pierre Laporte. The American Indian Movement (AIM), which began in the US, did influence Indigenous people in Canada, as the arrest of Dino and Gary Butler in 1981 in a shoot-out with the cops in Vancouver demonstrated. Dino Butler had been directly involved in the resistance to the FBI’s presence on Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota in the context of which Leonard Peltier was eventually sentenced for the killing of an FBI agent.

The women involved in the network of AIM supporters who flocked from the US for the Butler’s trial, stayed in our collective women’s house during their trial. This network included John Trudell and his wife, who were incredibly influential, in terms of our political and philosophical growth. Through John Trudell we realized that the most important goal was to protect the Earth and the Water. The Indigenous supporters from AIM never took a break from “politics” but began a campaign, “Water for Life” which is still a center-piece of Indigenous struggle today. We listened to everything John Trudell said as though he were Jesus, the son of God reincarnated. Any politics we developed that emphasized the importance of Mother Earth was directly related to the influence of the Indigenous people staying with us in 1981.

I believe Direct Action was also heavily influenced by the anarchist punk rock music scene that was active all along the west coast of Canada and the US. Gerry Hannah was the bass player and song-writer for the the anarchist punk rock band, the SubHumans who had the second highest following in the Canadian punk rock scene behind only D.O.A. When we met Julie Belmas, she was also a musician with deep roots in the anarchist punk rock scene.

The Red Army Faction was rooted in Marxism-Leninism, a more hierarchical and materialist political philosophy which, in many ways, was the antithesis of the spiritual and holistic Indigenous philosophy from which the American Indian Movement sprang. True to our anarchist punk rock and political influences, at least on a theoretical level, we aspired to operate as a collective with no official leadership. Leadership in anarchist collectives is supposed to be earned through the respect the grass-roots population have naturally bestowed upon those who have made good decisions. In other words, if a person shows that they make the best decisions because they work hard, listen and learn from others who have proven themselves already, their ideas will be listened to more earnestly and respectfully than someone who tries to earn a place of leadership through intimidation and fear.

However despite our differences in terms of anarchism and marxism, both Margrit Schiller and myself experienced the unchecked patriarchal dynamics that were rampant throughout the radical and revolutionary movements of the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s. This period represented the dawn of feminist awareness throughout Western Europe and North America. Feminist critiques of male domination and hierarchical leadership patterns can be found in the literature of the Black Panthers, RAF, Red Brigades and the IRA, just to name a few, but this represented a growing consciousness amongst women moreso than a change in practice. It would be decades before these feminist critiques made their way into the mainstream and even longer before women actually earned leadership roles by way of an enlightened, feminist, grassroots demographic.

There were major differences in terms of the prison conditions Margrit Schiller and I experienced. The RAF was clearly a bigger, more sophisticated and threatening organization to the State. The West German government designed and built a special courtroom and holding cells for the guerrilla prisoners at Stammheim, whereas our trial was held in a regular courtroom but with a larger police presence than normal, and both spectators and prisoners were subjected to more intensive daily surveillance rituals every time we entered or left the courtroom. As with all things security and surveillance, once the guerrilla movements in Europe and North America had died down, the new repressive surveillance and security regimes did not, but instead were adapted to control and surveil regular prisoners who the prison regime now classified or branded as “gang members” or “organized criminals.”

In your 2018 memoir, which covers from your arrest in January 1983 through to your parole suspension (re-incarceration) in 2012, you mention going inside as a young revolutionary in the 1980s with a lot of romantic notions about prisoners and how to conduct yourself in prison. Can you talk a little about what those ideas were and how they squared up with reality?

I still remember activists I knew back in the 70’s saying that if they went to prison, they would teach and organize the other prisoners to resist the prison regime. The way a lot of activists talked, you could tell they did not have a clue what the majority of prisoners were all about. They did not realize that most of the prisoners had been brought up in the criminal justice system, from foster homes when they were little children, where they were often abused sexually and/or physically, to juvenile detention centers as young adolescents. Eighty percent of all federally-sentenced women have been physically and/or sexually abused as children, a statistic that has been consistent for decades. So there is definitely a statistical link between criminalization and childhood abuse. Eventually these adolescents move on to their final destination, the federal penitentiary, where they will survive in a revolving door cycle: a couple of years in the “pen,” then a couple of years on “the street.”

A lot of people assume that people who have done time, or have “lived experience,” are stupid. Yes, “65% of the people entering prisons have less than a grade 8 education level of literacy skills, and 79% of people entering Canadian prisons don’t have their high school diploma,2 but school is not a reflection of an individual’s intellectual capacity. How well a person does in school is more a reflection of their capacity to function well in a system of memorizing and storing information by sitting in classrooms listening to lectures for long hours five days a week, and then perhaps another couple of hours in the evenings reading and writing. Characteristics that lend themselves to high grades are a person’s ability to be obedient and loyal to authority figures, especially those in places of so-called “higher learning.” The ability to be sedentary for many hours a day. The capacity to retain factual information in large quantities. Obviously this is not the same thing as intelligence.

Most prisoners have qualities that make up for their lack of schoolbook knowledge: resilience, adaptability, short-term memory capacity, ability to compartmentalize emotional trauma, determination, courage, and perceptiveness.

It would be a huge mistake to walk into any remand, provincial or federal prison and act like you are smarter or know more than the average prisoner, or to try to organize them or to even initiate conversations as though you know them. I am going to make some sweeping generalizations here, but they are based on statistics that are true for the vast majority of prisoners. As I stated earlier, prisoners are more perceptive than the average person: a survival skill they have honed in foster care, training schools and just plain old living on the street. People living in institutional settings learn very quickly that survival is dependent on how fast they can pick up on unspoken signals or language, and how to react to threatening signals. A whole book could be written on this topic. But your best bet, if you find yourself in a prison at any time in your life, is to shut up, watch, listen and learn. Do not speak unless spoken to, and quietly try to figure out who to align yourself with amongst the prisoner population.

Radical movements often experience tension between supporting political prisoners and supporting all prisoners. Some people see campaigning for political prisoners in particular as implicitly creating a division between people who don’t deserve to be in prison and those who do. What do you think about this question? How can political prisoners be supported without undercutting a movement for the freedom of all prisoners? Is it particularly important that we support people who are sent to prison as a result of movement activity?

I think the same philosophy that applies to how we, as political activists, engage with the people in general in our communities, also applies to how we engage with prisoners in general? Like the answers to most questions, the answer is not black and white.

If we see ourselves as a vanguard, more enlightened and entitled to political power than the average person, then of course, we will treat political and regular prisoners differently. I think the tendency to treat political prisoners as a special vanguard who must receive most of our attention is a philosophy that is compatible with Marxism-Leninism, and with those who believe in hierarchy. But anarchists, such as myself, do not see ourselves as special or necessarily more enlightened.. When it comes to living and surviving in prison, experienced prisoners are the PhD graduates of prisons whereas those who have never done time before are wearing the metaphorical dunce cap that only those with “lived experience” can see.

The values upon which our resistance is rooted are going to determine what kind of revolutionary society we create. It is very difficult to live by a different set of values than the mainstream society in which we were raised. From the moment we leave the womb, we are indoctrinated with the values of capitalism, to value material goods, to be competitive, and strive for power over others. We see ourselves as a superior species relative to every other living thing on this planet. If our resistance movement is not rooted in the alternative values of communalism, cooperation, and conservation, then we will essentially reproduce a new society that appears different, but in essence is the same. In other words, same game, same players…just different clothes, language, and hair styles.

The Russian revolution in 1917 was led by the Bolsheviks, who had studied Marxism and Leninism, leading them to believe that the transitional phase between capitalism and communism, would be led by the proletariat, the social class of industrial workers whose income is derived solely from their labor. This phase would be necessary to fight foreign capitalist armies who would no doubt present a unified international front against any successful national revolutionary forces that had acquired a grip on the capitalist economy of any single country. During this phase the proletariat are supposed to suppress resistance to the revolution by the bourgeoisie, destroy the social relations of production underlying the class system, and create a new, classless society. Unfortunately, this transitional phase was taken over by the Communist Party which claimed to represent the proletariat. It did not take long for this intoxicating power to get into their heads, to such a degree that they would not relinquish it and instead, the transitional phase known as the “dictatorship of the proletariat,” became a permanent dictatorship by the Communist Party.

The problem lies in the fact we are indoctrinated with capitalist values from birth within a capitalist economy. So the same individuals who are leading the communist revolutionary resistance, still have the ubiquitous vestiges of capitalism embedded in their behavior and thoughts. So it is important to prioritize reinforcing the new values and to embrace people in the general population so they too can become revolutionary individuals. If we do not believe in setting up a political or economic hierarchy, then we must embrace diversity, equality, and cooperation. A person’s skin colour, gender, sexual orientation, national origins, and physical capabilities are not relevant in terms of their capacity to make decisions, their ethical and moral choices, their work ethic, their courage, compassion and natural leadership qualities.

How can we expect to win any kind of revolutionary resistance, struggle or war if we do not have the involvement or support of the general population? And the only way that is going to happen is if we share the same values, goals and experiences. It is the same in prison. For example, let’s say some political prisoners are on a hunger strike with the goal of being taken out of isolation and placed in general population. If the whole prison population began a hunger strike in solidarity with our political prisoners, odds are the administration is going to capitulate a lot faster. Also, if we work with the other prisoners, then it is more likely they will understand and perhaps even embrace our goals and values.

Perhaps it sounds like a contradiction, but there are times when political prisoners will need special attention because there is no doubt that historically, the government has focused more attention on political prisoners than social prisoners because they are organized and more of a threat to the political/economic order. So there will be times when we must focus more energy on the struggles of political prisoners but that shouldn’t mean that we ignore the plight of social prisoners. Historically the repression focused on breaking down the will and identity of political prisoners, will eventually be used on social prisoners. Plus if we also focus on social prisoners, we can expect more of their support for the struggles of political prisoners…something the prison regime fears more than anything: a unified resistance of both social and political prisoners. That is our goal.

Prison issues have been a big part of your political life, even since before you were arrested. Beyond it being a form of social violence that you have experienced (and continue to be affected by), what draws you to this work? Aside from prisons, what other political questions or concerns do you find yourself particularly drawn to?

When I was younger, before I was in prison, I gravitated towards prison abolition work because I saw prisoners as one of the most abused people on the planet. My years in prison did not dispel this view. When I was finally released on full parole in the early nineties, I continued working towards prison abolition, not so much because I felt it was the most important issue, but more so because I had experienced prison first-hand and there were so few people with lived experience involved in the prison and capitalist abolition struggle.

It has been a long time coming, but I can honestly say that at this year’s Prisoners Justice Day in 2021, we had 10 women come to Kingston to the site of the now-closed Prison for Women, who had done significant periods of time both in P4W over 40 years ago, and the “new” federal prisons for women. Some of these women are now prison abolition activists and in my lifetime, it is rare to find people who have done time and are involved in prison abolition activism. I am very happy because it is extremely important that those with lived experience lead the prison abolition movement. By leadership, I mean those who have earned a place of respect and trust from the people with lived experience in prison as well as prison abolition activists who have no lived experience. These are natural “leaders” who have proven themselves to be wise, courageous, and knowledgeable as opposed to “leaders” who have risen through the ranks on the coat-tails of ambition, greed, and power.

However as I head into the last 2 decades of my life, I find myself being drawn more and more towards spending time trying to save what little wilderness and wildlife there is left. I find myself becoming more cynical about the potential for humans to actually create a revolutionary movement that is not materialistic, hierarchical and competitive. We, as a species seem to have this ingrained belief that we are special; smarter, and more self-aware or self-conscious than any other species of life. I don’t see any evidence of this. There is not a species on this planet so thoughtless and stupid as to shit and piss—metaphorically and literally— in their own drinking water and food. Despite repeated warnings from our own experts that we only have a decade left to prevent irreversible damage, we continue to consume natural resources at a suicidal rate, and refuse to even contemplate abandoning capitalism, an economic paradigm rooted in endless economic growth, consumerism and planned obsolescence. Is that a sign of an intelligent species?

However, I still believe in resistance, doing the right thing, and living according to our ideals, despite the possibility that we could fail, despite the possibility that a sixth extinction could wipe out most if not all of our species. There is never any guarantee that our efforts will be rewarded or that we will win in this struggle to eradicate capitalism. But this is not a gloom and doom message. This is a message of hope, resilience and reality. Do we want to be guided by fairy tales and wishful thinking? If so, we are doomed to failure. I believe that revolutionaries fight or struggle, not because we know we will win, but because we know it is right. We will always have a deep inner satisfaction knowing that we are fighting to save all oppressed creatures and our natural world from being consumed by this capitalist death culture. I would rather be executed knowing that I had lived according to my ideals and done what I believed was right, regardless of whether or not we are successful in our struggle against capitalism.

Notes

1 “Evidence suggests that women’s violent offences tend to be reactive in nature. As a result, violent crimes are more often committed against intimates, not strangers, and many of these women – some report the majority – experienced abuse at the hands of their partners before committing a violent offence. In 1998, the majority of the 68 women serving a life sentence for murdering their intimate partners had been abused by their partners prior to their offence.” https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/csj-sjc/jsp-sjp/rr03_la20-rr03_aj20/p9.html