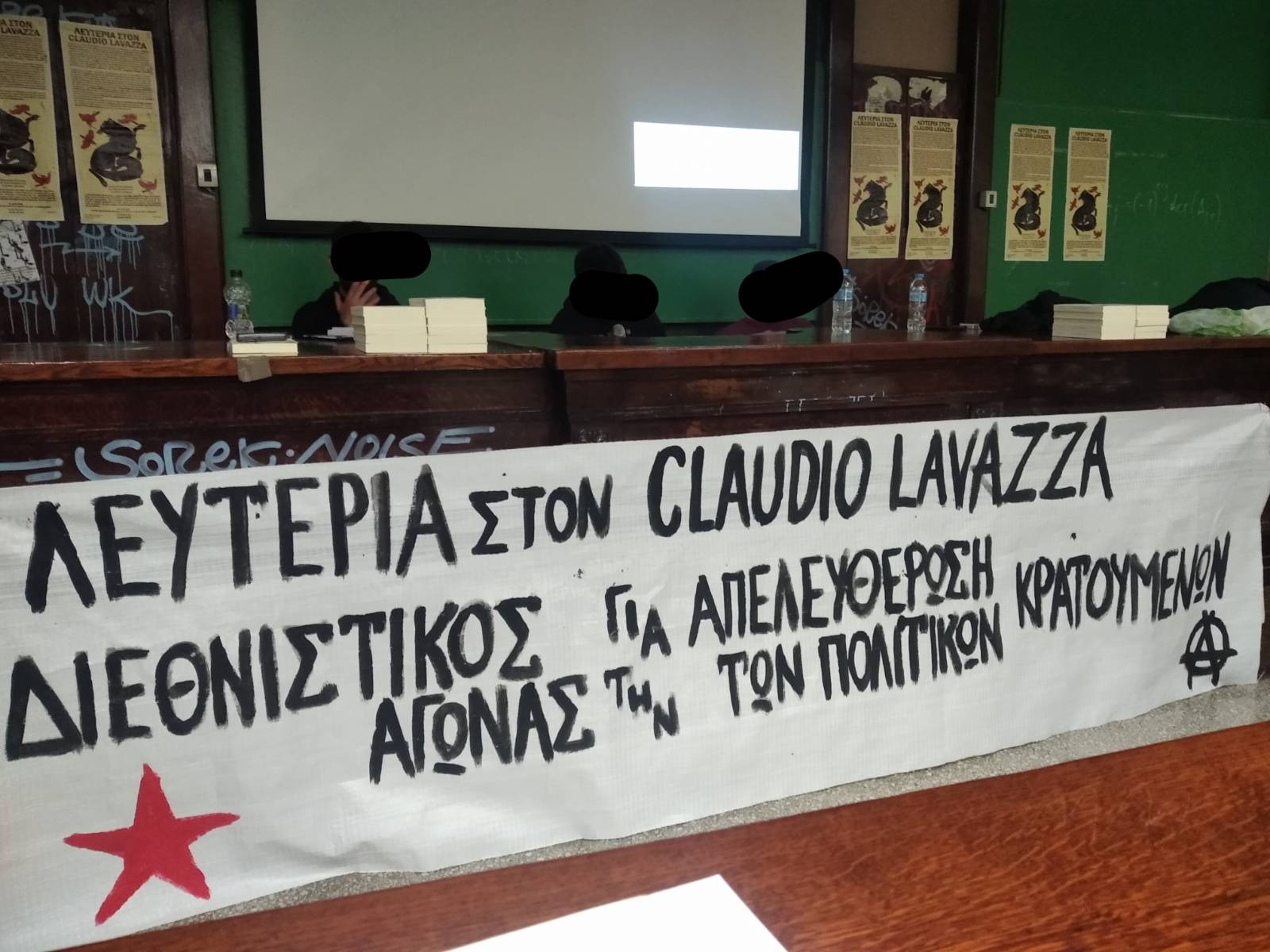

On Thursday, April 14th, the event of the Anarchist Initiative against State Killings, concerning the case of the anarchist comrade Claudio Lavazza, took place at the ASOEE with a relatively massive presence of comrades. The presentation was read as well as the transcript of an interview Claudio has given about his case and a video was shown concerning the expropriation of a bank in Cordoba and the subsequent confrontation with the police forces where he was arrested. Finally, comments and statements were made by comrades about the connection between Claudio’s experience of struggle, especially the years he participated in the Italian movement, and the present day, and it was decided to call an open assembly to organize a meeting at the French embassy on May 17, the day when the comrade’s appeal against the decision of the bourgeois justice system that forces him to serve another 5 years in prison until he is released will be heard. Below is the text of the submission where you can also find a Pdf file.

We will begin our submission by answering the simple question. Why do we consider solidarity with the comrade Claudio Lavazza important today? We answer by saying that in Claudio’s person we see a part of the revolutionary memory of contemporary revolutionary history.

Claudio from an early age was an insurgent proletarian who was actively involved in the mass movement and proletarian struggles of that period in Italy. But what was the historical context that fuelled the great struggles of that period?

“The post-war environment and the Cold War”

On a macro-level, the end of the Second World War and the new balances of terror that took shape in the international environment after the use of nuclear weapons of mass destruction in 1945 in Japan by the US and the subsequent nuclear arms race from 1949 onwards (when the USSR acquired the corresponding technology), influenced the intensity of the historical period of the Cold War, the milestones of which were the Greek civil war (1946-1949), the Chinese revolution in 1949, the Korean civil war (1950-1953), the lifting of the Berlin Wall in 1961 and the Cuban missile crisis a year later in 1962. These developments were decisive for the so-called transition to the so-called ‘peaceful coexistence’ process, which largely involved the establishment of strict non-intervention zones. These zones were in the perceived centre of the western and eastern world, i.e. almost the entire northern hemisphere of the planet, which of course did not prevent any of the main Cold War competitors from intervening even militarily in their own immediate zones of influence and even more so on the periphery of the perceived undeveloped world, moving the hot fronts of warfare to Latin America, Africa and Asia.

We ought to note here that in the decades after World War II, the Keynesian economic school, which emerged in the Great Depression of 1929 in the US, became particularly popular in the West and emphasized consumer power as an indicator of capitalist growth and prosperity of the centre. The basic rationale of this economic school was state interventionism as a tool for social welfare and better reproduction of the system. According to Keynes, the volume of employment depended on the total labour supply, the propensity to consume, the volume of capital investment, which created rapid class shifts as well as the swelling of the ‘labour aristocracy’ and the ‘social base of opportunism’ in the capitals of Western imperialism. To put it in more Marxist terms, if in the field of ideas the dominant ideology of the masses is determined by the material basis of the superstructure, when the material basis of the superstructure changes, the dominant ideology changes. In this way a new Belle Époque is rising in the West, in which the change in the degree of development of the productive forces was the fuel of capitalist development, while consumption becomes the dominant ideology of the masses, with the middle class created as a result of all the above factors.

All of the above had the result that, on the one hand, the traditional communist movements of the Western North entered into a process of aphasia, during which they were more or less fully integrated into the political scene of the country in which they were active (with the exception of Portugal, Spain and Greece, where the conditions due to civil wars and political instability were different) and, on the other hand, any radical anti-capitalist movements emerged in a break with the old institutions and representatives of the left, which began to look old and old-fashioned.

The new waves and tendencies of radical anti-capitalist movements that began to emerge in the West sought their own frameworks of intervention and conflict with the superstructure in its global dimension, and tried more or less to align themselves with the international developments of their time and synchronise themselves with anti-imperialist and anti-colonialist movements wherever they emerged.

‘The specificities of the Italian paradigm’

Italy as a country whose historical process of unification (“il Risorgimento”, or “The Revival”) ends only about seventy years before the outbreak of World War II is a geographic and historical peculiarity compared to other European countries, because of the social and class contradictions that divided not only social classes within Italy but entire geographical regions. The Italian north, which had been a predominantly Austro-Hungarian possession for decades, was at the centre of European developments from an early stage. Tied to the process of the industrial revolution, it followed a different economic and social evolutionary path that allowed it to move into modernity and liberalisation. On the other hand, the Italian south, which was largely rural and more remote from the changes taking place in continental Europe, remained more backward in its economic and social development.

These conditions had not changed rapidly by World War II and certainly played their own particular role in shaping a civil war situation within the country, with partisan communists on the one hand and regime fascists on the other, fighting alongside the battles being fought on all the other fronts of the war. After the fall of the Mussolini regime on 25 April 1945, which also marked the end of the war, there followed no purge of all those men and women who had collaborated with Mussolini’s fascist government. Many armed fascist groups continued their activities, taking advantage of the highly favourable penal code of the fascist regime that was still in force. A typical example is the amnesty granted to political prisoners. The number of fascists released from prison was 4127, while the number of resistance partisans was 152. A key area of interpretation of this period is the implementation of the Marshall Plan by the US to rebuild war-devastated countries in exchange for repression and the implementation of harsh anti-communist and anti-worker policies within the states as a precondition for the disbursement of the money. The post-war capitalist restructuring of Western Europe and the crushing of communist threats (internal enemy) was the formulation of the imposition of US economic and political influence on European soil.

“This plan included, among other things, economic aid to countries destroyed by the war, but also the removal from the structures of production of all communist workers who had experience of armed struggle against the Nazi and fascist forces. These individualities formed the basis of the workers’ movement in the main industrial triangle of the country (Turin, Milan, Genoa).

The workers who had fought in the ranks of the partisans had still kept the weapons they had used in the war, despite the PCI’s (Italian Communist Party) order to hand them over to put an end to the conflict. They were convinced that the elimination of the Nazi-Fascist plague was the intermediate stage for the great social emancipation of the proletariat. A conviction that remained alive until the assassination attempt against Palmiro Togliatti, a prominent CPI representative and Minister of Justice from 1945 to 1946, when the CPI was excluded from the government. These groups of militants and workers were the real thorn in the side of the plans for the formation of Italian big capital in the post-war period. For this very reason it was necessary for the capitalists to remove them from the world of work, so that they would have the scope to impose dismissals and iron discipline in the factories, thus ensuring high productivity with low wages.

Very important for the implementation of the capitalists’ plans was the repression of mass demonstrations. This was done either by shooting during the marches by the forces of class or by the action of fascist groups backed up by bouncers hired by businessmen. In these conditions of harsh repression the dead were numerous. There were more than 120 between 1946 and 1950, all those who had not bowed to the new production programme of the post-war era and who had to be punished harshly and exemplarily.” (Claudio Lavazza / My Pestiferous Life)

Strategy of Tension – Revolutionary Movement

As we have said, in post-war Italy there has never been a real purge by the capitalists of the state apparatus from the fascist elements that existed within it during the Mussolini period. These mechanisms were used by the deep state, the secret services and NATO in order to prevent the communist danger in Italy, as the CPI was a party with high figures and strong influence because of its glorious Partisan tradition. Unfortunately, this was happening in parallel with the prevalence of the reformist camp in the leaderships of the communist parties and the adoption of the line of peaceful coexistence of capitalism and communism and that the transition of power could be achieved beyond the revolution in a peaceful way through elections. Fortunately, however, several communist ex-partisans, simply rank-and-file cadres, distanced themselves from their party line and did not hand over the arms as indicated. Their reasons for doing so were mainly the need for self-defence against the fascist danger that was lurking, and the desire that the next raid on the palace of capitalist power would be successful. Some of these buried weapons of those fighters were passed on years later to members of the armed organizations of Italy to begin their own journey in revolutionary history.

At the end of the 1960s, and in particular in 1968, the movement began to organise in Italy with clear influences from May 1968 in Paris. And if the year for Italy was relatively quiet, 1969 saw the outbreak of a magnificent, massive and organised wave of workers’ strikes, demands and conflicts throughout Italy, with the country’s working class leading a series of mobilisations. From mass strikes to demonstrations in factories and organising workers into grassroots assemblies, and from clashes with fascists and the police to university occupations, the whole of Italy looked like a boiling pot.

Pieces of the regime, faced with the immediate danger to the capitalist order in Italy and subsequently to its geopolitical position as an outpost of NATO because of the tremendous momentum of the movement, resorted to the so-called strategy of tension. Thousands of members of neo-fascist organisations, often trained by the local and American secret services and with the immunity of the state apparatus, either join our comrades in the marches as assault battalions, or engage in a series of blind bombings with many victims in order to blame them on communists or anarchists so that the state can justify the state of emergency through which it will suppress the movement. At the same time the repression by the police escalated, resulting in bloody marches with victims on both sides.

Comrade Claudio was only 15 years old when members of the neo-fascist group Ordine Nuovo bloodied the Fontana Square in Milan with 17 dead and 88 injured. In the context of this attack and in order to justify the strategy of tension, the police arrested and subsequently executed the anarchist Giuseppe Pinelli. The following year there was an attempted coup d’état involving fascist elements of the army and police, with the involvement of the mafia, in order to avert the danger that the country had run into with the rise of the revolutionary movement in 1969. The strategy of tension continued unabated in the following years with constant bomb attacks on trains carrying strikers and demonstrators, with murders of comrades and comrades-in-arms, with blind bomb attacks with civilian victims. The highlight, of course, was the bomb attack by members of the neo-fascist organisation ‘Armed Revolutionary Cells’ on Bologna’s central railway station in August 1980, with 85 dead and over 200 wounded.

The movement’s response to the strategy of tension chosen by the state was to upgrade itself organisationally and politically in order to confront the state and the fascist groups. The movement was not dominated by those political currents that fall into the trap of introversion and agency; instead the revolutionary movement organised, armed and confronted the repression while crushing the radical right-wing groups in Italy on the street. The movement also avenged the assassination of our comrade Giuseppe Pinelli by executing with two bullets the inspector Luigi Calabresi, the man responsible for his murder.ve said, in post-war Italy there has never been a real purge by the capitalists of the state apparatus from the fascist elements that existed within it during the Mussolini period. These mechanisms were used by the deep state, the secret services and NATO in order to prevent the communist danger in Italy, as the CPI was a party with high figures and strong influence because of its glorious Partisan tradition. Unfortunately, this was happening in parallel with the prevalence of the reformist camp in the leaderships of the communist parties and the adoption of the line of peaceful coexistence of capitalism and communism and that the transition of power could be achieved beyond the revolution in a peaceful way through elections. Fortunately, however, several communist ex-partisans, simply rank-and-file cadres, distanced themselves from their party line and did not hand over the arms as indicated. Their reasons for doing so were mainly the need for self-defence against the fascist danger that was lurking, and the desire that the next raid on the palace of capitalist power would be successful. Some of these buried weapons of those fighters were passed on years later to members of the armed organizations of Italy to begin their own journey in revolutionary history.

At the end of the 1960s, and in particular in 1968, the movement began to organise in Italy with clear influences from May 1968 in Paris. And if the year for Italy was relatively quiet, 1969 saw the outbreak of a magnificent, massive and organised wave of workers’ strikes, demands and conflicts throughout Italy, with the country’s working class leading a series of mobilisations. From mass strikes to demonstrations in factories and organising workers into grassroots assemblies, and from clashes with fascists and the police to university occupations, the whole of Italy looked like a boiling pot.

Pieces of the regime, faced with the immediate danger to the capitalist order in Italy and subsequently to its geopolitical position as an outpost of NATO because of the tremendous momentum of the movement, resorted to the so-called strategy of tension. Thousands of members of neo-fascist organisations, often trained by the local and American secret services and with the immunity of the state apparatus, either join our comrades in the marches as assault battalions, or engage in a series of blind bombings with many victims in order to blame them on communists or anarchists so that the state can justify the state of emergency through which it will suppress the movement. At the same time the repression by the police escalated, resulting in bloody marches with victims on both sides.

Comrade Claudio was only 15 years old when members of the neo-fascist group Ordine Nuovo bloodied the Fontana Square in Milan with 17 dead and 88 injured. In the context of this attack and in order to justify the strategy of tension, the police arrested and subsequently executed the anarchist Giuseppe Pinelli. The following year there was an attempted coup d’état involving fascist elements of the army and police, with the involvement of the mafia, in order to avert the danger that the country had run into with the rise of the revolutionary movement in 1969. The strategy of tension continued unabated in the following years with constant bomb attacks on trains carrying strikers and demonstrators, with murders of comrades and comrades-in-arms, with blind bomb attacks with civilian victims. The highlight, of course, was the bomb attack by members of the neo-fascist organisation ‘Armed Revolutionary Cells’ on Bologna’s central railway station in August 1980, with 85 dead and over 200 wounded.

The movement’s response to the strategy of tension chosen by the state was to upgrade itself organisationally and politically in order to confront the state and the fascist groups. The movement was not dominated by those political currents that fall into the trap of introversion and agency; instead the revolutionary movement organised, armed and confronted the repression while crushing the radical right-wing groups in Italy on the street. The movement also avenged the assassination of our comrade Giuseppe Pinelli by executing with two bullets the inspector Luigi Calabresi, the man responsible for his murder.

“The Piazza Fontana massacre was interpreted by the majority of the people of the movement of the time as a “state massacre”, which was aimed at intimidating and terrorizing workers and students and stopping their struggles. After this attack, the talk of revolutionary violence, which was already at an advanced stage, was given a new impetus by various extra-parliamentary groups.

In the Proletarian Left this vision was translated into two operational options, which were put into practice through the newspaper “Nuova Resistenza”. The aim was therefore, on the one hand, to concentrate the concepts that were developing and, on the other hand, to promote experiences of struggle capable of breaking the social contract. It is worth noting that this collective declared itself ready to respond to the needs of the social struggles that were taking shape in the new political context. It was in this context and in this political and cultural context that the first “Red Brigade” was born at the Pirelli factory in Milan in November 1970.” (Claudio Lavazza/ My Pestiferous Life).

The rich social, political and cultural experience of the Italian revolutionary movement reached its highest point of struggle in the 70’s and 80’s, during which thousands of fighters stormed the heavens, keeping alive the vision of revolutionary overthrow. A true heroic generation of people who, with its contradictions, waged an unequal struggle that is perhaps the most acute and luminous example of prolonged revolutionary – class warfare in post-war Europe to this day. A galaxy of radical political currents that with their contradictions and differences had the will to really fight for the revolution. Nowadays, when memory is being transformed into numbers and codes in digital devices and the transmission of experience is shrinking in the wake of ideological shifts, the Italian revolutionary movement would be useful to study as it is a recent historical example from which we should draw lessons and inspiration for what a movement can achieve when it decides to take the revolutionary cause seriously.

Comrade Claudio therefore comes from the mosaic of the whole movement and the militant actions of that period. Non-attached at the beginning he participated in the factory mobilizations and strike pickets, he took part in clashes with the police and fascists in the street, and he had participated in actions of low guerrilla violence as well as in bank expropriations. After participating in the raging river of the 1977 autonomist movement, he enlisted in the revolutionary organisation ‘Armed Proletarians for Communism’. This organisation was involved in many expropriations and acts of revolutionary violence, culminating in the executions of the director of the Udine prison guards, Antonio Santoro, and Andrea Campagna, a vile torturer of prisoners and member of the police’s special anti-terrorist unit. In June 1979 Claudio Lavazza was arrested and taken to prison accused of being a member of the organisation, but due to lack of evidence he was released within a few months. But in March 1980 he was forced to go underground as he was turned in by a repentant member of the organisation. In his last year in Italy in 1981, Claudio, in an illegal situation, joined the Organized Communists for Proletarian Liberation (COLP), a project made up of members of various armed organizations that aimed to attack prisons and free political prisoners in order to inspire comrades in the hope of continuing the struggle. A project that would try to answer the problem of the thousands of militants in Italian prisons. Claudio participated in at least one of these actions, in the occupation of the prison of Frosinone on December 4, 1981, where two imprisoned comrades were released. The COLP then continued its action until 1984, the most significant moment being the bombing of the Rovingo prison in northern Italy in January 1982, which resulted in the escape of four comrades.

“Putting the question of the immediate release of our imprisoned brothers and sisters on the table today, just like yesterday, is one of the fundamental objectives in this social war (…) but here, while the system has evolved in terms of infrastructure and means of repression, we have remained in prehistory, without making the military and technological preparations to stand up to the imposing macro-prisons. It is almost impossible to attack these structures, cut off from villages and towns, as we did in Italy in 1981, finally releasing two prisoners. It is true that times have changed. Since we are talking about attacks on the system, even if we do not like to use terms such as military and technological preparation, it is obvious that we are talking about war and conflict, and in order to be successful it is necessary to rise to the occasion imposed by the technological progress of the repressive system. I’m not saying that it’s impractical to attack structures like macro-prisons, but the way we are, liberating prisoners and prisoners from within seems like an impossible dream.” (Excerpt from an interview with Claudio Lavazza)

“Kinetic retreat and unrepentant persistence”

In 1982 the comrade, under the weight of ongoing denunciations by repentant former members of armed organizations, seeks – like thousands of other comrades – refuge in France. At the time, France had a permissive policy, the result of Mitterrand’s social democratic government, whereby Italian political refugees who were not involved in illegal activities in the country would not be extradited to the Italian state. This policy from 1985 was concretised in the so-called Mitterrand Doctrine whereby those who had been involved in revolutionary organisations or other activities in Italy until 1981 and were now inactive could remain legally in France without risk of extradition to Italy.

But 1982 was not only an important year for Claudio, which essentially determined his later life to this day, but also for the entire revolutionary movement in Italy which in previous years had made its own proletarian assault on the heavens. The mass factory movement with its thousands of revolutionary industrial workers was broken up by the neoliberal reforms introduced by the Italian state. The pioneering (mainly communist) workers were either dismissed or arrested as members of armed organisations. The large industrial units were broken up into smaller ones with a twofold objective. On the one hand, to make the workers lose the class dynamics they had due to their large size, and on the other hand, to make it much more difficult than in the past to collectivise and acquire class consciousness. At the same time, specialisation and mechanisation of production in the factories was promoted, resulting in a further reduction and fragmentation of the workforce. It is important to understand the above reforms not only as part of the capitalist restructuring and the transition of capitalism to the neoliberal model that began in the 1980s, but specifically in the example of Italy, and as a shielding of the state against a movement that seemed capable not only of challenging the capitalist system but also of claiming proletarian (anti-)power according to the political schools of the subjects in question.

The mass movement, consisting mainly of communist, workers’ and anarchist groups, of many comrades on the periphery or even members of armed organisations and of course those who were moving in the field of workers’ autonomy, was also beginning to deflate. After an intense 12 years of constant militant presence. With fierce clashes – even armed – with cops and fascists. With occupations, expropriations, rent auto-reductions to meet proletarian needs. With a broader revolutionary counterculture that challenged the mass culture of capitalism we reached the ebb tide of the 1980s. The mass movement, influenced by neoliberal capitalist restructuring in the factories but especially by the ongoing repressive operations and the wave of penitents, was in decline.

The armed organisations with thousands of militant members and thousands of comrades in their periphery were also in deep crisis due to the multiple arrests and the constant denunciations of repentant former members. At the same time they were unable to respond to the wave of dismissals of the pioneer workers, the repression of the marches, the arrests but above all to inspire as in the past that the bet of the revolutionary overthrow of the regime was open and with it to update their political lines in order to respond to the challenges posed by the new era. This, based on the autobiographies, political texts and the testimonies of comrades and comrades-in-arms of the time, was the essential turning point that tipped the scales in the showdown in favour of the state. This led many to trivialise their history, to denounce their comrades in the face of the fear of prison. For many of them, the revolution that a short time ago seemed inevitable now suddenly seemed like utopia.

In our opinion, the criticism made of this period concerning the so-called militarization of the movement and the militarism introduced by the numerous armed organizations of the time as the main fact that contributed to the defeat of the movement, either does not answer the real issues of the time if it is made from an honest revolutionary position, or it is used by various parasites over the years on revolutionary movements who abhor the idea that in order to have a chance of victory and success a movement must be fully with responsible members governed by a strong sense of commitment, discipline and loyalty to the revolutionary cause. That can update its projections to the demands of each era without, of course, forgetting its history and the core of its existence. A movement that must constantly find the perfect balance between the theoretical constitution of its positions and its members and the attempt to make them the property of the specific subjects to whom it is addressed, specifying them according to the circumstances. Presenting them as feasible, necessary and advantageous in their class interests. A movement that stands on two feet with a dialectical and direct relationship between them. One foot is the organized mass movement that will participate in every field of the low-power social and class war that rages in the capitalist states with the aim of revolutionary overthrow of the system. The other leg is the armed preparation for the proletarian assault on the sky. The armed organisations in dialectical relation with the mass movement will take up the line of the mass movement and will be in the forefront of the conflict with the state, capital and their apparatus, while being prepared to take up the final confrontation with the state with the aim, together with the mass movement, of the armed overthrow of the regime.

What the various apologists for reformism, right-wingism and alternativism are often concealing when they refer to the defeat of the Italian revolutionary movement is that all the above-mentioned points were valid to a satisfactory degree in the so-called ” Years of Lead ” (1968-1980). The armed organisations consisted of thousands of members, many of whom participated in the processes of the mass movement. They had regular and regional members and cadres within the vanguards in the factories and in the working class and they made sure that on the one hand their word reached directly the large working class in Italy and on the other hand in most cases they kept up with the highly militant mass movement together. Certainly, as the comrades who participated in the processes of the movement of that period have attested, this dialectical relationship did not reach the degree required by the circumstances to threaten to the greatest extent the capitalist status quo in Italy, but it was not the only and certainly not the main reason for the retreat in the 1980s.

We must never forget that the acceptance of armed attacks and the massiveness of revolutionary organisations reached an unprecedented level for a country in the western world whose front was politico-ideological revolutionary movements without a national liberationist slant (as in the Basque Country and Northern Ireland for example) where it is de facto easier to achieve this rallying, and that the level of theoretical constitution of the armed organisations, their massiveness and their dialectical relationship with the movement was such that we believe that there was a serious question of overthrowing capitalism and winning the revolution in the country.

The historical transition of Italian capitalism of millions of industrial workers was a violent restructuring of immense dimensions that affected more than in other countries the whole of social relations within the capitalist structure, and therefore inevitably the revolutionary movement, which failed to answer this unsolvable puzzle. At the same time, the neoliberal reforms have altered the very structure of the working class and the poorer sections of the population in general. Privatisation, petty-bourgeois attitudes, and the struggle for self-interest altered the very social base that either participated in the movement or was the social terrain in which it operated.

Along with the above transition came the all-out attack by the Italian state with brutal and unprecedented methods, which in turn contributed to the retreat. Italy was literally transformed into a hybrid bourgeois-democratic capitalist state with strong elements found in dictatorial regimes. Italy in the late 1970s and early 1980s was an emergency state oriented towards the repression of the internal enemy. The police were largely militarised with special forces such as carabinieri. They could also arrest and search private places without a warrant except on suspicion of involvement in the movement. The suppression of demonstrations was even carried out with bullets. The anti-terrorist law also enabled the judicial authorities to detain without strong evidence of guilt thousands of comrades without any strong evidence of guilt, with the direct result that the prisons in Italy were filled with militants and there was an immediate issue of thousands of political prisoners.

Certainly the account of the action of the great revolutionary movement in Italy is a long discussion that cannot be put in absolute terms of victory or defeat. Nor do we consider it appropriate in the tragic condition in which the movements of Western Europe find themselves to express verbalistic opinions. But we want to remain the communicators of the experiences described by the participants themselves and to dwell on them, even if only superficially, in order to understand the decision of our comrade Claudio Lavazza to leave his country and take refuge, like thousands of other frustrated militants, in France.

France

In France in the early days, comrade Lavazza was looking for ways to return to Italy. “I was living away from my country and I was thinking of ways to return soon. But it seemed impossible. The wave of remorse had swept over any remaining safe places; spreading fear among the comrades.” (Claudio Lavazza/ My Pestiferous Life). In this terribly difficult and pressurized situation, many Italian political refugees legally integrated into French society, deciding to take advantage of the tolerant attitude of the French state, but as a consequence they were cut off from the important efforts made in Italy to reconstruct the movement and its armed organizations, especially until 1988, and from the prospect of forming revolutionary initiatives in France, as the necessary condition for not being extradited to the Italian state was that they had to have been able to take part in the revolutionary initiatives in France. The comrade responded to this difficult equation first with an individual willingness not to submit to the new conditions of life offered by the French state and then to transform this refusal into a more structured political activism by being drawn to anarchist ideology.

“I preferred to continue living in illegality. I did not like the idea of entering into a logic of compromise with the institutions of any government. It seemed to me like surrendering and declaring defeat.”(Claudio Lavazza/ My Pestiferous Life).

From 1982 to 1989 Claudio remained in illegality in France, trying in the first years to return and continue the struggle in Italy from a new angle. Disillusioned with the course things had taken and considering it impractical in the new circumstances to fight under the overall project of social revolution, he oriented himself towards the creation of a guerrilla group with the sole purpose of liberating comrades from prison.

“The climate in Italy was changing. The intensity of the attacks on the structures and persons of political, judicial and military power was decreasing. It was clear that few had the necessary support to continue fighting. For my part, I did not lose hope of returning to start a new struggle in a different light than in the past : to focus on the liberation of imprisoned comrades as the only focus of attack on the system. (…) Things were bad, but I was still thinking about continuing the struggle, even on my own, without anyone’s help or contribution. “ (Claudio Lavazza / My Pestiferous Life).

He left France in 1989 for Spain as a police check in Switzerland confiscated a sum of money that was discovered days later to have come from one of the biggest robberies ever committed in France, the so-called “Robbery of the Century”, where the robbers expropriated the vault of one of the Bank of France’s headquarters and took 13 million in today’s Euros. Although he had in the meantime managed to be released by the Swiss police and returned to France, he was now one of the number one wanted men in the country with his picture circulating everywhere.

Spain

The continuation of Claudio’s radical-subversive activity finds him in the 1990s in Spain where he is associated with anarchist militant organizations that develop armed activity in the country against the general atmosphere of Spanish national reconciliation, in effect sabotaging the peaceful transition to their own post-revolution and the consequent integration of radical movements with the exception of the armed organizations GRAPPO and ETA. The milestones of this action were the armed occupation of the Italian consulate in Malaga in December 1994 as a message of solidarity with the Italian anarchists on trial in the Marini trial and the armed robbery of the Santander bank in Cordoba on 18 December 1996, where it ended in an armed confrontation that resulted in two dead cops, the death of the money transfer clerk that the comrades had taken with them to escape and the serious injury and arrest of all those involved in the expropriation of the bank, including Claudio himself.

This expropriation and its outcome led the comrades to the dungeons of the Spanish Republic, where they were incarcerated for decades in the special FIES regime, an exclusionary regime for both disobedient prisoners who had no political activity and prisoners who were declared enemies of the regime and fought against it. FIES status means strict solitary confinement, 21 hours a day locked in your cell, censorship of correspondence, restriction of visiting hours and restriction of many activities within the prison that are allowed for the rest of the population. The comrades endured for decades this cruel regime of solitary confinement and constant torture, which was covered up by the state authorities and the Spanish media with unwavering dignity and militancy, constantly participating and organising stands and protests against the conditions of confinement imposed on them.

At this point it should be noted that these struggles were fought in a context in which a not insignificant part of the anarchist movement, most notably the Spanish anarcho-syndicalist CNT, had called for their political isolation, declaring that their actions had nothing to do with the anarchist movement and anarchist values, even going so far as to call for the sabotage of solidarity during their trial, saying that political demonstrations of solidarity and support discredit the anarchist movement and damage the mass social struggle. We will mention just one of the many examples in the book that show the depth and intensity of this division in relation to our comrade’s case. “It is worth highlighting the action of about 30 people. On the first day of the court, although they were not allowed to enter the courtroom, they demonstrated in the street in front of the court with a banner reading “They are not murderers, they are anarchists” and bearing the signatures of various acronyms of the libertarian movement, including the CNT (. ) Thus the Multidisciplinary Trade Union of Cordoba and the Regional Committee of the CNT in Andalusia issued texts in which they dissociated themselves from the aforementioned act of solidarity, citing the fact that none of the 30 people gathered in front of the court were members of the CNT. In these texts, they made no reference whatsoever to the fascist process of extermination to which the defendants were subjected and continued to be subjected during the hearing. They therefore concluded that the participants in the meeting were not linked to the CNT and demanded that the acronyms in question be removed, which is, if anything, absurd. It was also 12 months before this event, in April 1997, that the trade union in question organised a round of debates in Cordoba. A few weeks before it was due to take place, the participation of one of the guests was cancelled. The reason? The syndicate withdrew the invitation because the person in question was part of the group of lawyers defending the accused , who are victims of a fascist-style extermination. This move clearly shows the attitude of the CNT of Cordoba, which does not even need the pretext of ‘usurpation of acronyms’ to distance itself from the denunciation of such an event. Already 12 months ago it confirmed its shameless attitude with its decision to exclude one of the prisoners’ lawyers from participating in a cultural initiative.” (Claudio Lavazza / My Pestiferous Life)

Unfortunately, we see in this case too, something we know well from the Greek experience, that the prevalence of the international of reformism, integration and political disarmament of the anarchist movement, has resulted in political prisoners being discriminated against, slandered, isolated and left almost alone in the hands of state repression. A mentality that in most zones of Western capitalist centres unfortunately tends to end up appearing as the mainstream political representation of the movement, effectively cutting it off from a large part of its own history and tradition, distorting political meanings and significations, promoting a selective historiography that only highlights “what is convenient” and that leaves out anything that was moving in more militant directions. In Greece we experienced this – although not to such a great extent – with the convictions and provocative propaganda that followed the just execution of the two neo-Nazis in Neos Heraklion by the Struggling People’s Revolutionary Forces in November 2013. Then the domestic “anarchist” wing of the international one we are describing was quick to either condemn in terms of bourgeois legality or to act as an agent against the comrades who committed the action.

The example of the political isolation of the prisoners in the Cordoba robbery case is not unique in the history of the anarchist movement as this logic takes root and takes root diagonally and horizontally within radical movements, fostering a culture of permanent defeatism and victimisation which in turn leads to an inward fragmentation. The self-evident and practical solidarity both to themselves and to any individual or grouping that proceeds to such level of ruptures against the existing system of domination is therefore to a certain extent an attempt to stop the reformist scourge that is making repeated metamorphoses within the world of struggle.

Comrade Claudio himself, undaunted by these difficult circumstances, remained and remains to this day an unrepentant defender of his choices and action, facing a heavy price for this, as he is now one of the longest serving political prisoners in Europe.

Today

Claudio is currently incarcerated in France where he is serving a 10-year sentence for the Bank of France robbery and should have been released from prison in December when he completed 25 years in prison. However, the French prosecution authorities are denying this and are asking our comrade to serve at least another 5 years in real prison. The comrade has legally challenged the exceptional status he is experiencing and is demanding his release, and on 17 May he is due to have his appeal against this decision heard. The French state’s attitude towards Claudio exudes all the state retribution and authoritarianism that one encounters in dealing with unrepentant opponents of power. Criminal laws are reduced to rags and the famous ‘human rights’ are abolished. The bourgeois justice system becomes the vanguard of the “war on terror” and, wearing the mask of bureaucracy, wages a merciless war of attrition. A mechanism of cruel class domination and organised state violence that undertakes the extermination of its unrepentant opponents. We know that the main reason for their refusal despite so many years of imprisonment is that they never retreated from anarchist principles and values, that even from prison they continued to produce political discourse, to participate in hunger strikes against the FIES-type regime, to claim the connection between their own experience and the wider historical memory. He did not stop fighting and propagating with all his strength the necessity of the attack against the state and capital.

In closing this introduction we would like to mention that today’s event has 2 parts. The first part is to highlight the case of the comrade in order to exert pressure in the future to contribute with all our forces to the solidarity movement that demands the immediate release of the comrade. The second part concerns our deep conviction that a movement that forgets its history, that does not highlight people who have given their whole life selflessly in the struggle cannot be called subversive. It cannot produce an effect as it will be a mush that lacks the foundations needed to look history in the face, deflect it and ultimately claim to change it. Bringing to the fore the era of our dreams, the era of free people.

IMMEDIATE RELEASE OF THE ANARCHIST COMRADE CLAUDIO LAVAZZA

SOLIDARITY WITH POLITICAL PRISONERS

REVOLUTION FIRST AND FOREMOST

Anarchist initiative against the state murders

https://athens.indymedia.org/media/upload/2022/04/20/claudio-converted.pdf (in Greek)

Source: athens.indymedia