Our comrade Toby Shone was released from prison on 28th December 2022 under heavy restrictions (license conditions), which was overseen by a multi-agency team (MAPPA) including the National Security Division (counter-terror) and forced to live in a filthy bail hostel in Gloucester for 9 months. Since then he was abducted on 19th September 2023 at gun point by the armed scum of the anti-terrorist unit in between Gloucester and the Forest of Dean, along with being thrown back into prison once again.

We as anarchists in complicity with our comrade would like to highlight an intriguing and amusing event that occurred when Toby was still under bail and in conditions that were no better than an open prison.

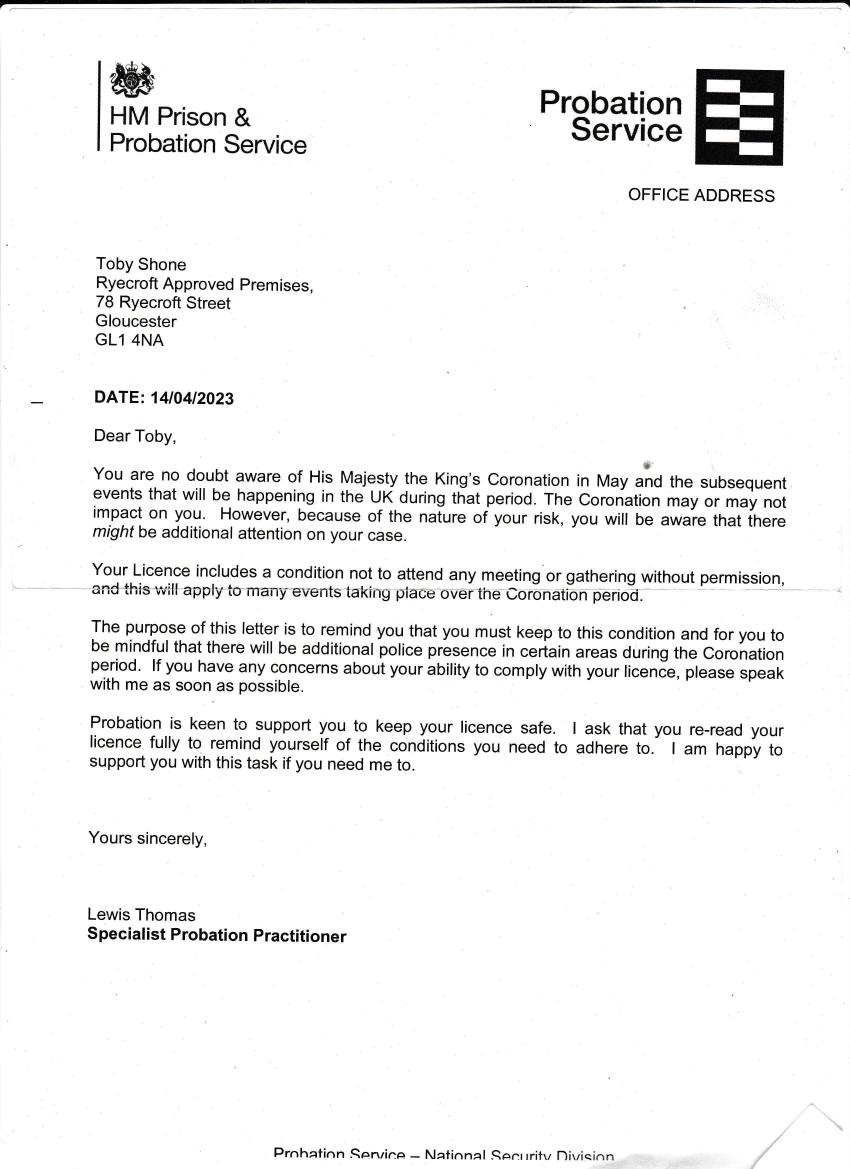

Added to this post is a letter dated 14th April 2023 received from Lewis Thomas the scum Probation Service – National Security Division officer who was managing Toby’s bail and conditions. It expresses in a comical language that puts across an image of wanting to help our comrade rather oppressing him, which was pretty much the tactic adopted generally by the goons of the National Security Division towards our comrade, as if anarchism and holding revolutionary ideas is a mental disease that needs to be treated. For us this letter highlights even more the climate that is starting to begin in the United Kingdom that anarchism is to be combined alongside fascist and Islamic ideologies as extremism and terrorism.

In the spirit of this comical letter and in the age-old tradition of assassination that the UK state and all states around the world should fear, we give a limited chronological account of the history of attempted and successful assassinations of monarchs by anarchists, revolutionaries and rebels who made the fear change sides, with the propaganda of the deed.

God will not save the King!

Anarchists in complicity with anarchist comrade Toby Shone

The History of Regicide by Anarchists, Revolutionaries & Rebels

(Attempted) Napoleon III of France, 1858

On the evening of 14 January 1858, as the Emperor and Empress were on their way to the theatre in the Rue Le Peletier, the precursor of the Opera Garnier, to see Rossini’s William Tell, Felice Orsini Italian revolutionary, leader of the ‘Carbonari’ and his accomplices threw three bombs at the imperial carriage. The first bomb landed among the horsemen in front of the carriage. The second bomb wounded the animals and smashed the carriage glass. The third bomb landed under the carriage and seriously wounded a policeman who was hurrying to protect the occupants. Eight people were killed and 142 wounded, though the emperor and empress were unhurt. They judged it best to proceed to the performance and appear before the public in their box.

Orsini himself was wounded on the right temple and stunned. He tended his wounds and returned to his lodgings, where police found him the next day. Orsini was sentenced to death and went calmly to the guillotine on 13 March 1858. Accomplices Pieri was executed and Gomez condemned to hard labour for life. Di Rudio was sentenced to death, which was commuted to life imprisonment on Devil’s Island near Cayenne, whence he escaped and later went to America.

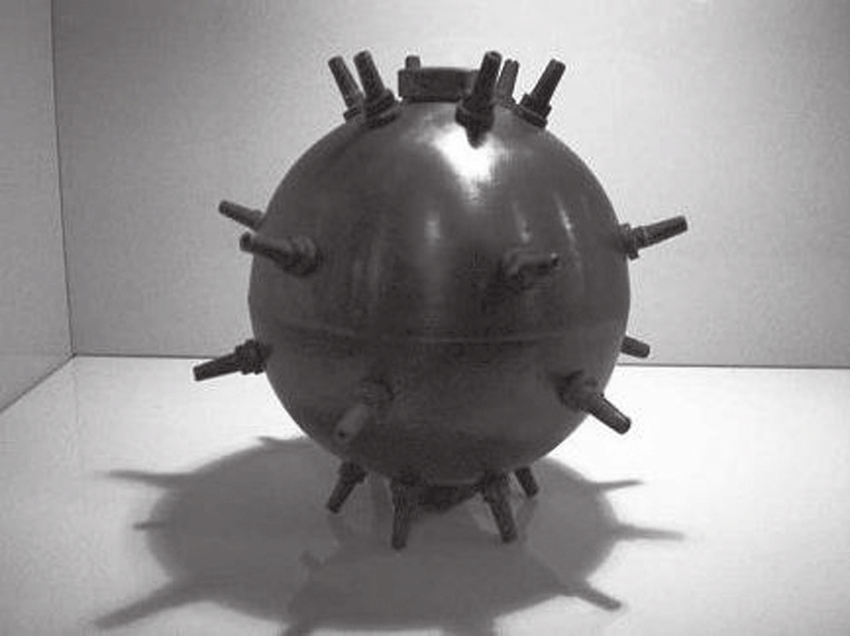

The improvised bomb that Orsini used was infamously named after him the ‘Orsini Bomb’ (pictured below). The weapons were somewhat commonly used by anarchists in the latter half of the 19th century in Europe, and surplus bombs were also used by the Confederacy during the American Civil War. The design is reminiscent of modern impact fused grenades, such as the Soviet RGO hand grenades. Orsini bombs were designed to remove “the uncertainty of slow burning fused weapons”. In several plots, including an attack at Rossini’s Opera William Tell at Liceu Theater in 1893 by anarchist Santiago Salvador; resulting in the death of 20 people and wounding 30.

(Two Attempts) Wilhelm I, German Emperor, 1878

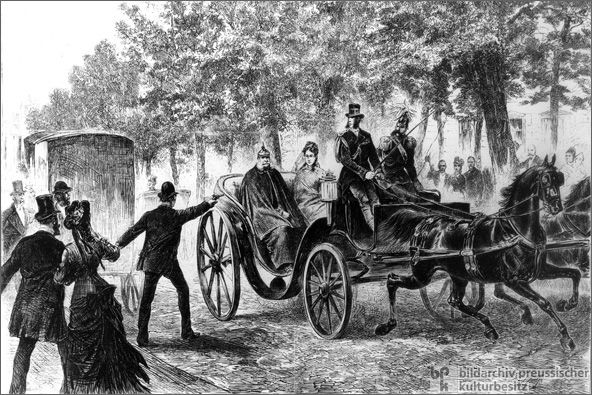

On 11 May 1878, a plumber & propaganda of the deed anarchist named Emil Max Hödel failed in an assassination attempt on Wilhelm in Berlin. Hödel used a revolver to shoot at the then 81-year-old Emperor, while he and his daughter, Princess Louise, paraded in their carriage. When the bullet missed, Hödel ran across the street and fired another round which also missed. In the commotion one of the individuals who tried to apprehend Hödel suffered severe internal injuries and died two days later. Hödel was seized immediately. He was tried, convicted, sentenced to death, and executed by beheading at Moabit prison on 16 August 1878.

A second attempt to assassinate Wilhelm was made on 2 June 1878 by Karl Nobiling, who had flirted with socialist ideas in his student days. As the Emperor drove past in an open carriage, the assassin fired two shots from a shotgun at him from the window of a house. Wilhelm was severely wounded and was rushed back to the palace. Nobiling shot himself in an attempt to commit suicide. While Wilhelm survived this attack, the assassin died from his self-inflicted wound three months later.

Chancellor Otto von Bismarck used the actions of Nobiling and Hödel as justification to implement the repressive Anti-Socialist Laws in October 1878. These laws were the first amongst many that led to what we now know in the present as Anti-Terrorist laws.

(Attempted) King Umberto I of Italy, 1878

On 17 November 1878, Umberto I and his court were parading in Naples. The anarchist Giovanni Passannante was among the crowd, waiting for the right moment to act. While the king was on Largo della Carriera Grande, he approached his carriage, faking a supplication; suddenly, he pulled out a knife and attacked him yelling, “Long live Orsini! Long live the Universal Republic!”

Umberto I managed to deflect the weapon, receiving a slight wound on his arm. Queen Margherita threw a bouquet of flowers in his face and shouted: «Cairoli, save the king!». Cairoli grabbed him by his hair, but the prime minister was wounded in his leg. The captain of the cuirassiers, Stefano De Giovannini, was able to hit Passannante on the head with a sabre, and he was arrested. Passanannte had tried to kill the king with a knife with a blade of 12 cm (4.7 in) for which he traded his jacket. The weapon was wrapped in a red rag on which was written, “Death to the King! Long live the Universal Republic! Long live Orsini!”

During the trial, held on 6 and 7 March 1879, Passannante stated that he had acted alone. He claimed that the ideas of Risorgimento had been betrayed and that the government was indifferent to the impact on already poor people of increases in the flour tax. Passannante was sentenced to death on 29 March 1879, although capital punishment was expected only in instances of actual regicide. His sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.

He was imprisoned in Portoferraio on the island of Elba, off the Tuscan coast, in a small and dark cell below sea level, with no toilet facilities and in complete isolation. His mental condition deteriorated in these harsh conditions of solitary confinement and reportedly he was brutally tortured. He fell ill with scurvy, became infested with taenia solium and lost body hair. His skin became discoloured and his eyes were affected by the lack of light. The anarchist was transferred to the asylum of Montelupo Fiorentino. The physicians there were unable to reverse his mental and physical deterioration. Passannante died in Montelupo Fiorentino, at the age of 60, five days before his 61st birthday.

Unfortuantly that was not the end of the torture and idignity of Passante. Even after his death, his corpse was beheaded, and his head and brain became the subject of the study of criminologists. In 1935, his brain and skull, preserved in formaldehyde, were sent to the Criminal Museum in Rome, where they were displayed for over 70 years.

As we have seen with the repression of our comrade and other cases of comrades internationally over history, anarchism has always been deemed by the enemy as a disease, a mental illness that is to be studied & cured by scientits and psychologists, that a so called defect in the brain is responsible for revolutionary spirit rather than the inhuame conditions we all face under their tortourous system. Nothing less is expected from the tortourers, the psychopaths of authority, the criminologists who deserve our bullets and bombs as much as the kings, queens, politicians, cops and judges.

“The resigned majority is guilty. The minority has the right to remind them.”

Tsar Alexander II of Russia, 1881

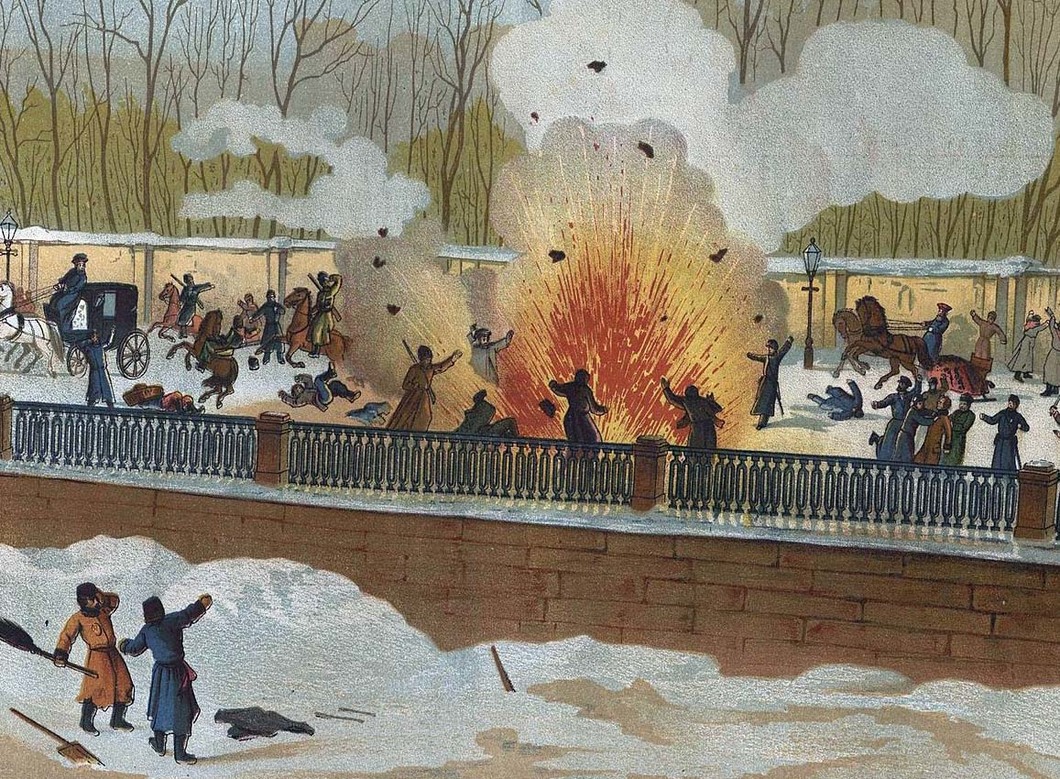

After a total of 5 previous attempts by individuals and groups, on 13th March 1881, Alexander was finally assassinated in Saint Petersburg. As he was known to do every Sunday for many years, the emperor went to the Mikhailovsky Manège for the military roll call. The street was flanked by narrow pavements for the public. A young member of the Narodnaya Volya (“People’s Will”) movement, who espoused acts of political violence in an attempt to destabilize the Russian Empire and spur insurrection against Tsarism, stepped forward to attack the Tsar. Much of the organization’s philosophy was inspired by nihilist Sergey Nechayev and “propaganda by the deed.” The member in question, Nikolai Rysakov, was carrying a small white package wrapped in a handkerchief. He later said of his attempt to kill the Tsar:

After a moment’s hesitation I threw the bomb. I sent it under the horses’ hooves in the supposition that it would blow up under the carriage… The explosion knocked me into the fence.

The explosion, while killing one of the Cossacks and seriously wounding the driver and people on the sidewalk, had only damaged the bulletproof carriage, a gift from Napoleon III of France. The emperor emerged shaken but unhurt. Rysakov was captured almost immediately. Police Chief Dvorzhitzky heard Rysakov shout out to someone else in the gathering crowd. Dvorzhitzky offered to drive the Tsar back to the Palace in his sleigh. The Tsar agreed, but he decided to first see the culprit, and to survey the damage. He expressed solicitude for the victims. To the anxious inquires of his entourage, Alexander replied, “Thank God, I’m untouched”.

Nevertheless, a second young member of the Narodnaya Volya, Ignacy Hryniewiecki, standing by the canal fence, raised both arms and threw something at the emperor’s feet. He was alleged to have shouted, “It is too early to thank God”. Dvorzhitzky was later to write:

I was deafened by the new explosion, burned, wounded and thrown to the ground. Suddenly, amid the smoke and snowy fog, I heard His Majesty’s weak voice cry, ‘Help!’ Gathering what strength I had, I jumped up and rushed to the emperor. His Majesty was half-lying, half-sitting, leaning on his right arm. Thinking he was merely wounded heavily, I tried to lift him but the czar’s legs were shattered, and the blood poured out of them. Twenty people, with wounds of varying degree, lay on the sidewalk and on the street. Some managed to stand, others to crawl, still others tried to get out from beneath bodies that had fallen on them. Through the snow, debris, and blood you could see fragments of clothing, epaulets, sabres, and bloody chunks of human flesh.

Later, it was learnt there was a third bomber in the crowd. Ivan Emelyanov stood ready, clutching a briefcase containing a bomb that was to be used if the other two bombers failed. Alexander was carried by sleigh to the Winter Palace to his study where almost the same day twenty years earlier, he had signed the Emancipation Edict freeing the serfs. Alexander was bleeding to death, with his legs torn away, his stomach ripped open, and his face mutilated.

On 25–26 August 1879, on the anniversary of Alexander’s coronation, the 22-member Executive Committee of Narodnaya Volya resolved to assassinate Alexande in the hopes that it would precipitate a revolution. Over the subsequent year and a half, the various attempts on Alexander’s life had ended in failure. The Committee then decided to assassinate Alexander II on his way back to the Winter Palace. Andrei Zhelyabov was the chief organizer of the plot. The group had observed his routines for a couple of months and was able to deduce the alternate intentions of the entourage. If the Tsar was to go by the Malaya Sadovaya, the plan was to detonate a mine placed under the street. To further ensure the success of the plot, four bomb-throwers were to loiter at the corners of the street; after the explosion, all of them were to close in on the Tsar and use their bombs if necessary. If, on the other hand, the Tsar passed by the canal, the bomb-throwers alone were to be relied upon. Ignacy Hryniewiecki (Ignaty Grinevitsky), Nikolai Rysakov, Timofey Mikhailov, and Ivan Yemelyanov had volunteered as bomb-throwers.

The group opened a cheese store in the Eliseyev Emporium on Malaya Sadovaya Street, and used one of the rooms to dig a tunnel extending to the middle of the street, where they would lay large quantities of dynamite. The hand-held bombs were designed and chiefly manufactured by Nikolai Kibalchich. The night before the attack, Perovskaya along with Vera Figner (also one of seven women on the Executive Committee) helped assemble the bombs. Zhelyabov was to have directed the bombing, and he was supposed to assail Alexander II with dagger or pistol in case both the mine and the bombs were unsuccessful. When Zhelyabov was arrested two days prior to the attack, his wife Sophia Perovskaya took the reins.

After the assination the thrower of the fatal second bomb, Hryniewiecki, was carried to the military hospital nearby, where he lingered in agony for several hours. Refusing to cooperate with the authorities or even to give his name, he died that evening. In a vain attempt to save his own life, Rysakov, the first bomb-thrower who had been captured at the scene, cooperated with the investigators. His testimony implicated the other participants, and enabled the police to raid the group’s headquarters. The raid took place on 15 March, two days after the assassination. Helfman was arrested and Sablin fired several shots at the police and then shot himself to avoid capture. Mikhailov was captured in the same building the next day after a brief gunfight. The tsarist police apprehended Sophia Perovskaya on 22 March, Nikolai Kibalchich on 29 March, and Ivan Yemelyanov on 14 April.

Zhelyabov, Perovskaya, Kibalchich, Helfman, Mikhailov, and Rysakov were tried as State criminals by the Special Tribunal of the Ruling Senate on 26–29 March and sentenced to death by hanging. The sentence was carried out on 15 April 1881. In the case of Hesya Helfman, her execution was deferred on account of her pregnancy. Alexander III later commuted her sentence of death to katorga (forced labor) for an indefinite period of time. She died of a post-natal complication in January 1882, and her infant daughter did not survive much longer.

Yemelyanov was tried the following year and was sentenced to life imprisonment at hard labor; however, he received a pardon from the Tsar after serving 20 years. Vera Figner remained at large until 10 February 1883; during this time she orchestrated the assassination of General Mayor Strelnikov, the military prosecutor of Odessa. In 1884, Figner was sentenced to die by hanging which was then commuted to indefinite penal servitude. She likewise served for 20 years until a plea from her dying mother persuaded the last tsar, Nicholas II, to set her free.

Alexander II’s death led to his succession by Alexander III, with the formal coronation ceremony of the Tsar postponed for more than two years due to security concerns. He chose to abandon his father’s reforms and went on to pursue a policy of greater autocratic power. The assassination triggered major suppression of civil liberties in Russia, and police brutality burst back in full force after experiencing some restraint under the reign of Alexander II, whose death was witnessed first-hand by his son, Alexander III, and his grandson, Nicholas II, both future emperors who vowed not to have the same fate befall them. Both of them used the Okhrana to arrest protestors and uproot suspected rebel groups, creating further suppression of personal freedom for the Russian people. A series of anti-Jewish pogroms and antisemitic legislation, the May Laws, were yet another result. Finally, the tsar’s assassination also inspired anarchists to advocate “‘propaganda by deed’—the use of a spectacular act of violence to incite revolution.

Empress Elisabeth of Austria, 1898

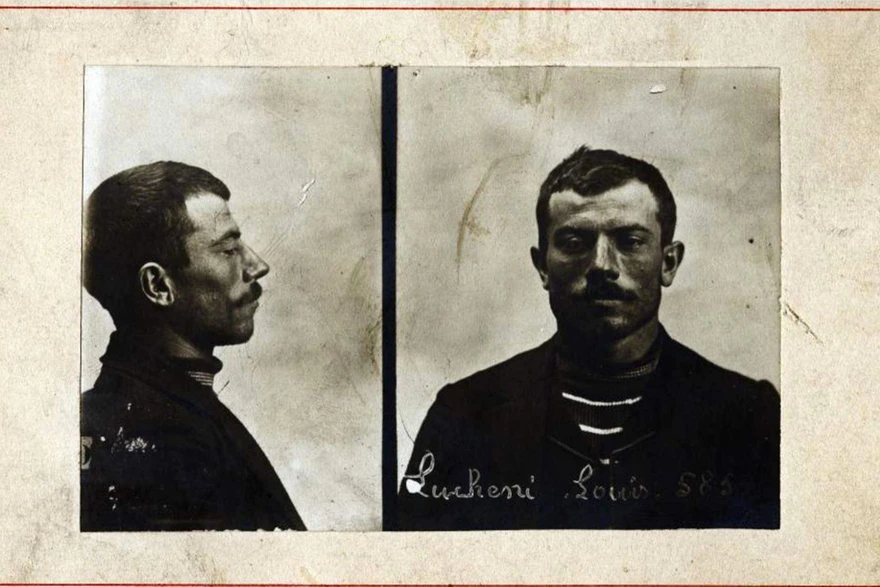

At 1:35 p.m. on Saturday 10 September 1898, Elisabeth and Countess Irma Sztáray, her lady-in-waiting were walking along the promenade alongside the Lake of Geneva in Switzerland. The 25-year-old Italian anarchist Luigi Lucheni approached, attempting to peer underneath the empress’s parasol. As the ship’s bell announced the departure, Lucheni seemed to stumble and made a movement with his hand, as if he wanted to maintain his balance. In reality, however, in an act of “propaganda of the deed”, he had stabbed Elisabeth with a sharpened needle file that was 4 inches (100 mm) long (used to file the eyes of industrial needles) that he had inserted into a wooden handle.

Lucheni originally planned to kill the Duke of Orléans, but the pretender to France’s throne had left Geneva. Failing to find him, the assassin selected Elisabeth when a Geneva newspaper revealed that the elegant woman traveling under the pseudonym of “Countess of Hohenembs” was the Empress of Austria.

I am an anarchist by conviction… I came to Geneva to kill a sovereign, with object of giving an example to those who suffer and those who do nothing to improve their social position; it did not matter to me who the sovereign was whom I should kill… It was not a woman I struck, but an Empress; it was a crown that I had in view.

Lucheni was brought before the Geneva Court in October. Furious that the death sentence had been abolished there, he demanded that he be tried according to the laws of the Canton of Lucerne, which still had the death penalty, signing the letter: “Luigi Lucheni, anarchist, and one of the most dangerous”. Since Elisabeth apparently preferred the common man to courtiers, was also known for her charitable works, and considered a blameless target, Lucheni’s sanity was questioned initially. He was declared to be sane, but was tried as a common murderer, not a political criminal. Incarcerated for life, and denied the opportunity to make a political statement by his action, he attempted to kill himself with the sharpened key from a tin of sardines on 20 February 1900. Ten years later, he hanged himself with his belt in his cell on the evening of 16 October 1910, after a guard confiscated his uncompleted memoirs.

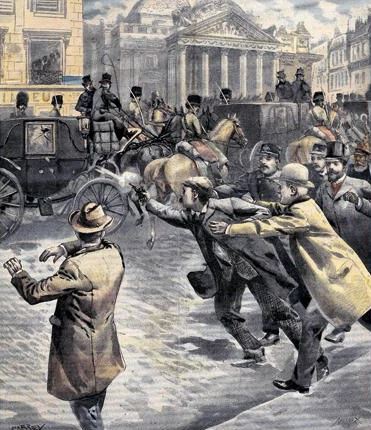

(Attempted) King Edward VII of United Kingdom, 1900

Jean-Baptiste Victor Sipido was a Belgian anarchist who became known when he, then a young tinsmith’s apprentice, with his pockets stuffed with Anarchist literature, attempted to assassinate the then Prince of Wales, who would become King Edward VII, at the Brussels-North railway station in Brussels on 5 April 1900.

Accusing the Prince of causing the slaughter of thousands during the Boer War in South Africa, the fifteen-year-old leaped onto the foot board of the royal compartment right before the train left the station and fired two shots through the window. Sipido missed everyone insideand was quickly wrestled to the ground.

The assassination attempt and the following trial is notable mostly for the acquittal of Sipido. His guilt was quite obvious, but he was less than 16 years old. The jury “held that by reason of his age he had not acted with discernment and could not be considered doli capax” or legally responsible. The court did not even detain Sipido in a reformatory. After the trial, Sipido immediately crossed the border to France.

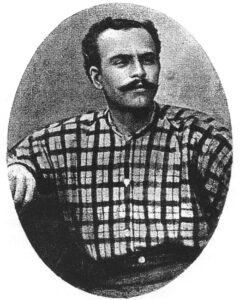

(Succeeded) Umberto I of Italy, 1900

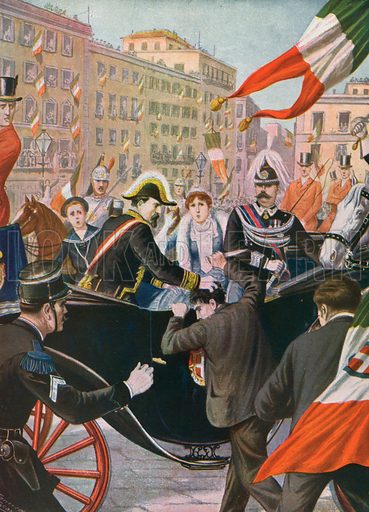

After receiving news of the Bava Beccaris massacre, where hundreds of protesting workers were killed and wounded by the Italian Army, Gaetano Bresci, an anarchist, swore revenge against Umberto I of Italy, who he called the “murderer king”. With money from ‘La Questione Sociale’, he bought a .38 caliber revolver and a one-way ticket back to Italy, informing his wife that he was returning in order to take care of family business.

In Monza Bresci learnt that the King of Italy was due to attend a gymnastics competition, while staying at the local Royal Villa. Bresci found a room near the Monza train station and waited to strike. For two days, he scouted the area and inquired for information about the King’s activities.

After preparing his weapon and thoroughly grooming himself, on the morning of 29 July 1900, Bresci left his hotel intent on assassinating the King at the end of the contest. He spent most of the day walking around town and eating ice cream, briefly stopping for lunch with a stranger, who he told “Look at me carefully, because you will perhaps remember me for the rest of your life.” That evening at 21:30, Umberto took his car to the stadium, where he was to hand out medals to the competition’s athletes at 22:00. There were very few Carabinieri stationed along the route and not enough to effectively carry out crowd control at the stadium.

Bresci had positioned himself along the road that led out of the stadium, in order to give himself a chance at escape, but the excited crowd swept him within three meters of the King’s car and blocked his way out. While amongst the crowd, Bresci drew his revolver and shot Umberto. As the King lay dying, Bresci was accosted by the angered crowd, but was arrested by a marshal of the Carabinieri before he could be lynched. He accepted arrest without resistance, declaring:

“I did not kill Umberto. I have killed the King. I killed a principle.”

The government of Italy suspected that Bresci had been a part of a conspiracy, but no evidence of such was found, indicating that Bresci had acted alone. He was consequently sentenced to life imprisonment for murder and confined on Santo Stefano Island, where he was found dead of an apparent suicide within the year. After his death, Bresci gained the status of a martyr within the Italian anarchist movement, who defended his regicidal act. Bresci even inspired some anarchists, such as Leon Czolgosz, to carry out their own acts of propaganda of the deed. Italian anarchists erected a monument to Bresci in Carrara, despite attempts to block it by the government.

(Attempted) Leopold II of Belgium, 1902

On 15 November 1902, Italian anarchist Gennaro Rubino attempted to assassinate Leopold, who was riding in a royal cortege from a ceremony at Church of St. Michael and St. Gudula in memory of his recently deceased wife, Marie Henriette. After Leopold’s carriage passed, Rubino fired three shots at the procession. The shots missed Leopold but almost killed the king’s grand marshal, Count Charles John d’Oultremont. Rubino was immediately arrested and subsequently sentenced to life imprisonment. He died in prison in 1918.

Gennaro’s past was shaky at best, while serving in the Italian army as a young man, Rubino was condemned to five years’ detention for writing a subversive newspaper article. In 1898, he was arrested again during bread riots in Milan. Rather than serving a lengthy prison sentence, Rubino fled the country. He first took up residence in Glasgow, Scotland and then moved to London. He was unable to find work, however, until offered assistance by the Italian Embassy. He was then employed by the Italian Secret Service to spy on anarchist organizations in London. He was dismissed from the job, however, once embassy officials discovered that he sympathized with the anarchists.

In May 1902, Rubino’s employment with the Italian Secret Service was uncovered, and he was denounced by the international anarchist press as a spy. Evidently, Rubino then resolved to commit an assassination in order to prove his allegiance to the anarchist cause. As he wrote in a letter to his former comrades, “perhaps tomorrow or after, I will be able to prove my rebellion in a manner more consistent with my and your aspirations.” According to later police interrogations, he considered killing King Edward VII of the Uited Kingdom, but decided against it due to the strong feeling of the English people in favour of the monarchy. Instead he chose King Leopold II of Belgium.

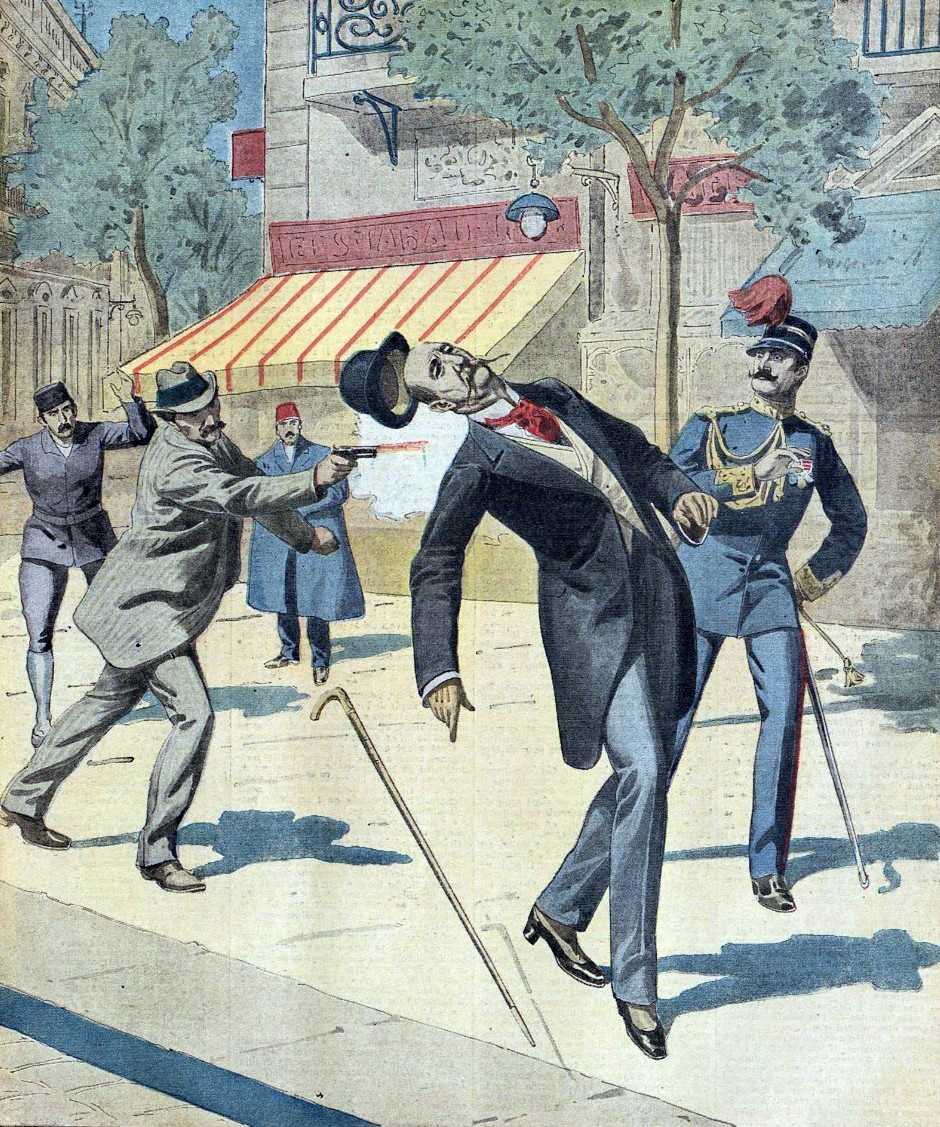

Carlos I of Portugal, 1908

On 1 February 1908, the royal family was returning to Lisbon from the Ducal Palace of Vila Viçosa in Alentejo, where they had spent part of the hunting season during the winter. On their way to the royal palace, the open carriage with Carlos I and his family passed through the Terreiro do Paço fronting on the river. In spite of recent political unrest there was no military escort. While they were crossing the square at dusk, shots were fired from amongst the sparse crowd by two republican activists, Alfredo Luís da Costa and Manuel Buíça.

Buíça, a former army sergeant and sharpshooter, fired five shots from a rifle hidden under his long overcoat. The king died immediately, his heir Luís Filipe was mortally wounded, and Prince Manuel was hit in the arm. The queen escaped injury. The two assassins were killed on the spot by police, and an innocent bystander, João da Costa, was also shot dead in the confusion. The royal carriage turned into the nearby Navy Arsenal, where, about twenty minutes later, Prince Luís Filipe died. Several days later, the younger son, Prince Manuel, was proclaimed king of Portugal. He was the last of the Braganza-Saxe-Coburg and Gotha dynasty and the final king of Portugal.

George I of Greece, 1913

On 18 March 1913, several months after capturing Thessaloniki from the Ottoman Empire during the First Balkan War, King George I was out for a late afternoon walk in the city and, as was his custom, lightly guarded. Encountering George on the street near the White Tower, Alexandros Schinas shot the king once in the back from close range with a revolver, killing him. Schinas was arrested and tortured. He said he acted alone, blaming his actions on delirium brought on by tuberculosis. After several weeks in custody, Schinas died by falling out of a police station window either as murder or suicide.

The details of Schinas’s life before the assassination are unclear. His occupation and native Greek birthplace are unconfirmed. According to Schinas, he finished medical school but practiced medicine without authorization because he could not afford to pay for a medical degree. Several years before the assassination, Schinas may have left Greece for New York City, working in two hotels before returning in February 1913. Some contemporary sources reported that he advocated anarchism (possibly propagada of the deed) or socialism, and ran an anarchist school that was shut down by the Greek government. Other sources suggested he was mentally ill or exacting revenge against the king for denying a request for financial assistance. Other theories have claimed that Schinas acted as a foreign agent, but no direct evidence supporting these theories has emerged.

During the night I was waking up, like I was being taken over by madness. I wanted to destroy the world. I wanted to kill everybody, because the whole of society was my enemy. Luck wanted that during this psychological condition to meet the King. I would have killed my own sister if I had met her that day.

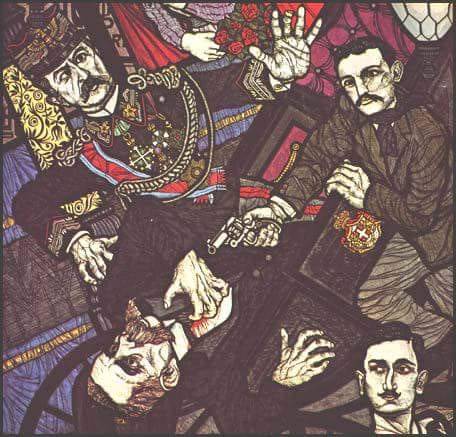

Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, 1914

Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife, Duchess Sophie Chotek, arrived in Sarajevo by train shortly before 10 a.m. on 28 June 1914. Their car was the third car of a six-car motorcade heading towards Sarajevo Town Hall. The car’s top was rolled back to allow the crowds a good view of its occupants.

Gavrilo Princip and the five other conspirators lined the route. They were spaced out along the Appel Quay, each one with instructions to assassinate the Archduke when the royal car reached their position. The first conspirator on the route to see the royal car was Muhamed Mehmedbašić. Standing by the Austro-Hungarian Bank, Mehmedbašić lost his nerve and allowed the car to pass without taking action. At 10:15 am, when the motorcade passed the central police station, nineteen-year-old student Nedeljko Čabrinović hurled a hand grenade at the Archduke’s car. The driver accelerated when he saw the object flying towards him, and the bomb, which had a 10-second delay, exploded under the fourth car. Two of the occupants were seriously wounded. After Čabrinović’s failed attempt, the motorcade sped away and Princip and the remaining conspirators failed to act due to the motorcade’s high speed.

After the Archduke gave his scheduled speech at Town Hall, he decided to visit the victims of Čabrinović’s grenade attack at the Sarajevo Hospital. To avoid the city centre, General Oskar Potiorek decided that the royal car should travel straight along the Appel Quay to the hospital. However, Potiorek forgot to inform the driver, a Czech named Leopold Lojka, about this decision. On the way to the hospital, Lojka, following the original plan, turned onto a side street where Princip was in front of a local delicatessen. After the Governor shouted at him, Lojka stopped in front of a shop and began to reverse. As he did so the engine stalled and the gears locked. Princip stepped forward, drew a Browning semi-automatic pistol, and at point-blank range fired twice into the car, first hitting the Archduke in the neck, and then hitting the Duchess in the abdomen. They both died shortly after.

The Austro-Hungarian government who saw Serbia’s nationalist aspirations as a threat to its own multi-ethnic empire, used the assassination as the perfect pretext to take action against Serbia. A chain of events triggered the July Crisis which led to the outbreak of World War I. On 28 July, 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, followed by the declarations of war by Germany, France, Russia and Great Britain.

The eventual assassin Gavrilo Princip was a Bosnian Serb revolutionary nationalist student, who was part of the Young Bosnia, a secret local society aiming to free Bosnia from Austrian rule and achieve the unification of the South Slavs. Princip was influenced by by a spate of assassination attempts against Imperial officials by Slavic nationalists and anarchists. He had been close to various student groups that had emerged interested in movements such as romantic nationalism, nihilism, or anti imperialism, while at school and was also exposed to socialist, anarchist, and communist writing. Princip started to associate with like-minded young nationalist revolutionaries and came to admire Bogdan Žerajić, a Bosnian Serb who had attempted to assassinate the Austro-Hungarian Governor of Bosnia and Herzegovina, before taking his own life. Žerajić, who was from Herzegovina like Princip, came to epitomize, in the eyes of many, the ideal of self sacrifice. On the anniversary of his death, Serb youths from Sarajevo started to visit his grave to lay flowers. This is where, after spending nights reflecting at the grave, that Princip resolved to participate in his own attack.

Unfortunatly it is also well known that Princip and his co-conspirators were helped by the Black Hand, a Serbian secret society with ties to Serbian military intelligence, who provided the conspirators with weapons and training before facilitating their re-entry into Bosnia.

Alexander I of Serbia, 1934

On 9th October 1934, while Alexander was being slowly driven in a car through the streets of Marseille along with French Foreign Minister Barthou, a gunman, the Bulgarian Vlado Chernozemski, stepped from the street and shot the King twice and the chauffeur with a Mauser C96 semiautomatic pistol. Alexander died in the car and was slumped backwards in the seat with his eyes open. Barthou was also killed by a stray bullet fired by French police during the scuffle following the attack. Lieutenant-Colonel Piollet, having finally managed to turn his horse, struck the assailant with his sword. Ten people in the procession were wounded, including General Alphonse Georges was hit by two bullets as he tried to intervene, and nine people in the crowd who came to see the king, four of them fatally. Just hours later, Chernozemski died in police custody.

The assassin was a member of the pro-Bulgarian Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO or VMRO) and an experienced marksman. Immediately after assassinating King Alexander, Chernozemski was cut down by the sword of a mounted French policeman, and then beaten by the crowd. By the time that he was removed from the scene, the King was already dead. The IMRO was a political organization that fought for the liberation of the occupied region of Macedonia and its independence.

King Abdullah I of Jordan, 1951

On 20 July 1951, while visiting Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, Abdullah was shot dead by a Palestinian nationalist. The assassination has been attributed to a secret order based in Jerusalem known only as “the Jihad”, a possible precursor to the Muslim Brotherhood. He was shot while attending Friday prayers at Al-Aqsa Mosque in the company of his grandson, Prince Hussein. The Palestinian gunman fired three fatal bullets into the King’s head and chest. Prince Hussein was hit too but a medal that had been pinned to Hussein’s chest at his grandfather’s insistence deflected the bullet and saved his life. Abdullah’s assassination was said to have influenced Hussein not to enter peace talks with Israel in the aftermath of the Six-Day War in order to avoid a similar fate.

Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma, 1979

We couldn’t resist this one, not a king, but who cares?

Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma, a close relative of the British royal family, was assassinated on 27 August 1979 by Irish republicans and volunteers of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA). A 50lb gelignite bomb was placed on Mountbatten’s boat while it was harboured overnight in Mullaghmore Peninsula in County Sligo, Republic of Ireland. It was detonated several hours later, after Mountbatten and his family and crew had boarded it and taken it offshore. Mountbatten was found alive by fishermen who rushed to the site of the explosion, but he died before reaching shore.

The assassination took place during The Troubles, a conflict between republicans and unionists in Northern Ireland following the Partition of Ireland. The IRA claimed responsibility three days after the bombing, describing the attack as “a discriminate act to bring to the attention of the English people the continuing occupation of our country.”

Mountbatten was a great-grandson of Queen Victoria, second cousin to Queen Elizabeth II, and uncle to her husband Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. As Chief of the Defence Staff, Mountbatten served as head of the British Armed Forces from 1959 to 1965, having previously headed the Royal Navy as the First Sea Lord. Sinn Féin vice-president Gerry Adams said that Mountbatten was a military target in a war situation.

The assassination marked an escalation of the conflict, with the IRA committing their deadliest attack on the British Army (the Warrenpoint ambush) on the same day as the assassination. Thatcher changed Britain’s approach by treating IRA prisoners as criminals rather than like prisoners of war and was herself the target of an assassination attempt five years later.

(Attempted) King Charles III of United Kingdom, 1994 & 2010(?)

In 1994, while still Prince of Wales, Charles was in Australia for Australia Day celebrations when David Kang, a former University Student frustrated with the status of Cambodian Asylum seekers in Australia, jumped up onto the stage where the Prince was and fired 2 shots from a starter pistol at the Prince. The Prince was quickly pulled out of harm’s way by his security team who then apprehended Kang. The subsequent investigation revealed that Kang had sent over 500 letters in regards to Cambodian Asylum seekers to various news organizations and public officials. Of these letters, the only response he received came from Prince Charles, who had his secretary mail a response. Although unconfirmed, many believe that it was this response that led Kang to fixate on the Prince and use him as a martyr for his cause.

This is not the only time King Cahrles’ life has been threatened. Not quite an assassination attempt, but we fondlly remember how in 2010 during the December student protest in London that was held in response to the vote in Parliament to raise tuition fees in universities. How one amongst many marauding groups of protestors that had managed to break out of or not be trapped in the kettle surrounding the main protest in Parliament square that descended into a pitched battle with cops including on horseback, managed to surround Charles and his wife Camilla as they were leaving a theatre performance in their Royal Royce limousine. Blood curdling shouts of “OFF WITH THEIR HEADS!” accompanied by banging on the windows sent the fear of death into both of the royals. If only the chants had become true…