The Internet of bodies: the body as a technological platform

Introduction

It has not even been ten years since the Internet of Things made headlines and fueled the dreams of technologists around the world. Smart clothes that can measure your mood and update your cell phone, smart glasses with which you can overlay reality with a second layer of your own, e.g., with personalized realities, smart and inexpensive light bulbs charged with carrying the burden of your eco-consciousness by turning on only when you are in the room or when you give the command from the controller of your life aka smartphone, smart coffee makers, ingenious mugs, wi-fi-enabled sinks, and the list goes on. All this new “smart” and illusory life promised by the universal interconnection of everything on the Internet has turned out to be, at least so far, a mere fantasy. But is this proof of the failure of the Internet of Things? In a sense, the answer should be yes (again, at least for now), at least if one is to take such promises at face value. On the other hand, the Internet of Things can be considered as much of a “failure” as any new model of an automobile-based society is a “failure” because its drivers end up spending most of their time moving at the pace of a sloth on Alexandra rather than with feline grace on open roads, vast expanses of open country, or meandering, scenic roads perched on green mountains, as they should, given the commercials. The crucial difference in the case of the Internet of Things, which will provide the measure of any failure or success, is that it was not simply an attempt to promote a product or even a range of products. What was widely promoted or even mandated was not so much and not only the lures of smart devices, but the very idea of universal connectivity, the notion that information can be drawn from anything and that this information can be valued, exploited and enhanced.

There have been many, too many, probably the vast majority of individuals in Western societies, who have seemed all too willing to take the bait of all kinds of smart devices. Finding themselves with the hook of universal interconnectivity stuck in them, perhaps not yet sufficiently aware of the consequences of the position they have found themselves in. The oceans of psycho-intellectual novocaine in which they swim daily (courtesy of social media and subscription lobotomy platforms) do not leave them much room to maneuver. The extent of this retreat of conscience and panicked concession of battlefield positions that would once have been considered non-negotiable has become evident, if nothing else, with the recent issuance of health certificates. The docile readiness with which the subjects display the symbols of their unworthy conformity to a paranoid regime (even for unnecessary movements, such as those related to work or studies) is a low point but not the nadir of political and aesthetic-moral decline; at the other end of the sewer are those who assume the role of controllers, not infrequently enjoying their role, even if they do not openly admit it, perhaps not even to themselves (their tone of voice and body language are, however, irrefutable witnesses). A marvelous social condition that allows microclimates and alveolus to be created everywhere, within which the mushrooms of petty authoritarian attitudes acquire the status of the self-evident: the teacher checks the pupils (a mischievous person might say, “this is not a new role for teachers”), the clerk checks the teacher when he shows up as a customer, the waiter checks the clerk when he goes to buy coffee, etc. Everyone is given the opportunity to assume the role of the examiner; but no one is spared the role of the examined: in other words, the definition of the cannibal condition.

A nontrivial reminder: all these things owe their “success” in large part to the fact that they are mechanically mediated. The smartphones that promised the blossoming of a life in which everything would be available at (or even before) the push of a button seem to have first spread the manure of social barbarism in the form of mutual surveillance. It is obvious that without the ability to instantly scan and identify a certificate, the entire “medical” surveillance regime would be unstable and to such an extent that it might eventually collapse. But who would dare to oppose such practices among those who, for the sake of any free “convenience,” have become spineless data bleeders through their interconnected devices of all kinds?

The body as a field of intervention

This intersection of medical “care” and surveillance with network technologies is neither temporary nor occasional, although it is often presented as such. It is a key axis of the capitalist march toward the fourth industrial revolution that is sometimes developed under various labels. Two of these are precision medicine, which is concerned with operating on a somewhat more tangible and concrete level, and post-humanism, for which no metaphysical vanity and no religious soteriology are extraneous and inappropriate.1 As if these were not enough, a third similar label has circulated recently: we refer to the so-called “Internet of Bodies.” We are not fans of the inflated creation of new terms for whatever a bureaucrat in a think tank or a researcher seeking new funding might come up with. The Internet of Bodies seems at first to be a similar case of a term with no particular object coming to recycle old material. While this is true to some extent, at a second look the term actually seems to signal a new twist in the relationship between body surveillance and electronics that deserves a closer look. Unlike precision medicine, the Internet of Bodies is not just about health problems, but potentially anything that might involve the body, both healthy and sick. And as an extension in some ways of post-humanism, it not only envisions the biological body as perpetually upgradeable, but at the same time as “open” to the outside world, as an infinite source of information, as a node within a feedback mega-machine (the good old cybernetic dream).

But what exactly is the Internet of Bodies? If the Internet of Things was the idea that every object in the world can be equipped with sensors that can connect to the Internet, the Internet of Bodies takes it a step further by treating the body itself as such an “object.” The body is now understood as a “technological platform “2 on which various types of devices can be deployed and attached. This was more or less the purpose of the current of self-quantification and the quantified self. For the Internet of Bodies, however, self-quantification is only the first step. The integration of the quantified and hacked bodies into a communication network, their almost anatomical openness to the outside world, even in the form of an information flow, is the second step.

The earliest references to the term Internet of Bodies (at least based on our research) seem to date back to 2014 and were related to Google’s ambitions to develop embeddable devices such as contact lenses containing nano-circuits and hair-sized antennas.3 Despite its catchy and sensationalist nature, as a term it has not gained particular momentum in the years immediately following. Its wider establishment occurred in two stages, with a slight delay. First, it was used by academic, U.S. law professor Andrea Matwyshyn in an insightful article in which she describes, categorizes, and analyzes, often very critically, the devices in question and the legal consequences of their proliferation in the future.4 This article has since been a constant reference point in all discussions related to the Internet of Bodies. In its second year, this term seems to be exploding in popularity starting in 2020. The leading role has now been taken by think tanks (such as RAND5), organizations such as the World Economic Forum6 and techno-scientific associations through their journals.7 The fact that this term has suddenly found itself on most official lips and pens at the very time when the pandemic of totalitarianism in the guise of the coronavirus has challenged fundamental notions of the body and its autonomy cannot be considered simply coincidental. It is not a coincidence of time. Those who thought that coronavirus management was simply about the virus itself and possible ways to deal with it will soon learn that it was actually about their whole body. And the Internet of Bodies will be one of the terms of the polynomial by which the bodies of the subjects of Western societies will be described and circumscribed.

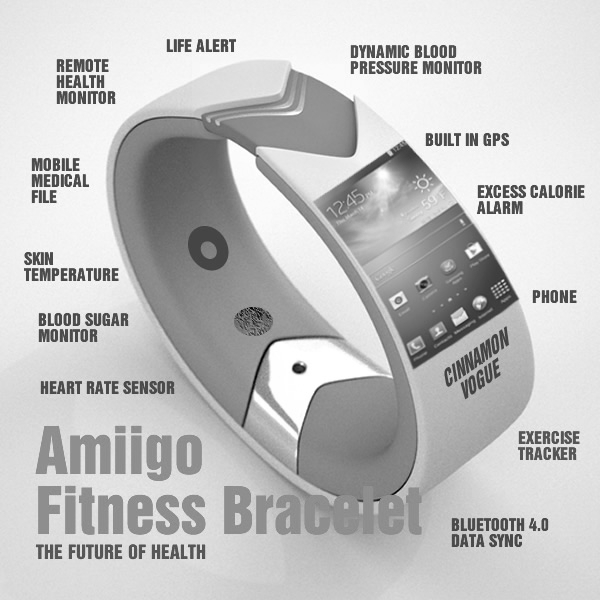

Matwyshyn’s article cited above attempts, in addition to providing a definition of the Internet of Bodies, to make an initial genealogical classification of relevant devices. As the first generation of Internet Of Bodies (IoB) devices it cites those that interact with the body while remaining external to it (body-external). Examples abound: from Google’s smart glasses that have been badly retired (but only temporarily, in our opinion) to all kinds of wearables to record physical activity or even electronic skin devices that are attached to normal skin and take medically relevant measurements. Here it is important to understand that many of these devices are not even considered medical devices and therefore their sale and use do not require approval from the relevant bodies. However, they almost always have the ability to collect, process and store recorded data, away from the control of users. The question of ownership, title and possession of this data is still in a legal vacuum, which of course does not prevent the companies behind it from embarking on unprecedented operations of primitive accumulation of “digital capital,” given the ignorance and sloth that users display on such matters.

The second generation of IoB devices now involves devices that, in order to function, must be “installed” on the user’s body by means of invasive techniques that break through the dermal boundaries of the body (body internal). Cochlear implants (and sensory damage repair devices in general), smart pacemakers, electronic pills with the ability to emit information after ingestion, artificial organs (3D printer products) are just some of the relevant examples. Although they are not new as ideas (conventional pacemakers have a long history), what now distinguishes them from their ancestors is their ability to interface with the outside world in the first instance; and in the second instance, the ability to receive commands from the outside world and adapt their behavior, either on the basis of such external commands or even spontaneously on the basis of internal instructions, since many of them have their own computing power, sometimes equipped with artificial intelligence algorithms.8 It goes without saying that even with this type of device there is still the problem of the legal status of the collected data. In fact, since in many cases we are dealing with the control of vital body functions, if the software of these devices is considered to be the property of the manufacturer, the issue is taken to an even deeper level: companies, according to their own dispositions, intentions and refusals to maintain, remove or update the relevant software packages, acquire de facto property rights over the users’ bodies; in extreme cases even life and death rights. Under no circumstances, however, should it be assumed that this generation of IoB devices is limited to therapeutic or preventive medical applications. For example, smart contact lenses that can project information or even entire virtual worlds directly into the eye are catching on for the entertainment and socialization part; a part that in the long run could prove more important and profitable than the strictly medical part.

Finally, the third generation, which is considered the least developed at present, includes those devices that aim to combine biological and artificial intelligence; in other words, devices that are connected to the users’ nervous system and can thus be put under the direct control of their “minds.” This category includes various types of prosthetic limbs that can be moved by means of electrodes connected to the remaining nerves of the amputated limb. Once again, however, it is by no means necessary for the use of such devices to remain within a strictly medical-therapeutic framework. There is no doubt that the field of cognitive and neural enhancement and optimization will appeal to entire populations, not only the sick, but also the healthy-or rather the predominantly healthy. At present, existing devices do not appear to provide capabilities to dive into the deep structures of the nervous system; they are generally limited to what are called “brain-computer interfaces” that operate through a tangential connection to the nervous system (e.g., via electrodes). However, research digging into the inner workings of the brain is proceeding rapidly,9 with no certainty as to when its results will find their way into the real world. If we take the case of the coronavirus and the preventive genetic preparations presented as a salvation against it as a good example of what is to come, then we should not expect extensive safety checks for these devices that aspire to latch onto the nervous system. If the immune system has been thrown in the dustbin as obsolete with such ease, there is no reason why the same should not happen with the nervous system.

The Great Reset

It should be obvious from the above that we are not only facing a paradigm shift in terms of understanding health and thus appropriate therapeutic techniques, but also an equally important restructuring of the understanding of the body and by extension also of the self. The body no longer has inviolable boundaries, no longer constitutes a sanctuary that can be accessed only in very specific circumstances and with the utmost precautions, it is not even something I own exclusively, according to the doctrines of classical liberalism. The body opens to the world, it becomes almost transparent, from a sphere folded in on itself it becomes an unfolded surface of which every inch is available for measurement and examination. There is no longer a horizon of facts, however nebulous, beyond which rests a hard core of subjectivity. A multitude of bodily functions (or even organs) can be replaced by others, artificially reinforced or even allowed to atrophy to the point of being considered “obsolete.”

Such a development may be seen as a good thing by some or even as a confirmation of the theories of the so-called extended mind (see the work of “philosophers of the mind” Andy Clark and David Chalmers) according to which what we call “mind” is not limited to the confines of the brain or even the body, but includes parts of the external world (e.g., the pages on which I am writing this article and you are reading it are part of my mind and your mind, respectively). Such theories arise from an in-principle correct disposition of the critique against conceptions that see the mind as a fundamentally closed and completely individuated unit (thus recalling Leibniz’s metaphysical ontology) that only later establishes relations with its environment. But to the extent that they suffer from a lack of dialectical sensitivity — and this is a common condition — they can easily end up with extreme idealism (Berkeley-like). Moreover, the notion of an extended body (to paraphrase the term “extended mind”) that the Internet of Bodies proposes essentially nullifies the earlier notion that saw the body (and the self) as an unmodified totality, the result of millions of years of biological evolution. In other words, the body was not seen as a mere cumulative assemblage of individual and independent organs and functions that could be reorganized at will, but as a totality with its own peculiar teleology under which individual organs fell — and here one could also invoke the Spinozian notion of conatus, that is, the effort that every living being makes to maintain its existence as a totality. According to the Internet of Bodies, Spinoza’s conatus is nothing but an illusion; the body (can and will) is in constant communication with its environment, receiving commands from it and in constant readiness to respond. One does not know (at least to our simplistic eyes) what the consequences of such a “breaking of the vessels” of the human body (and probably not only) would be.10 At the very least, one could imagine severely disturbed and psycho-intellectually mutilated beings in complete confusion of identity and unable to synthesize their experiences into a coherent understanding of the world and themselves. Which in turn is absolutely certain to bring serious disturbances even in what we call physical health; an organism that is unable to distinguish with any degree of clarity between the “outside” and the “inside” is an organism whose immune system will be in a permanent crisis and whose nervous system will be in a manic-depressive state: either in hyper-stimulation trying to respond incessantly to new stimuli and commands or in catatonia, resigning itself to the demand for constant action, reaction and feedback.

The blow against the sense of self and the dissolution of body-based subjectivity will not come, however, only through the collapse of the sense of wholeness of individual biological organisms. Since the ambitions of the Internet of Bodies have a strong flavor of post-humanism, pointing to the overloading of the concept of health toward the “ideal” of continuous improvement, this implies that any division (class and otherwise) among human subjects may also begin to acquire a biological dimension.11 If some subjects, because of their artificial “enhancements” and upgrades, possess a radically different range of experiences from that of the more “old-fashioned” models, without even being able to shed these augmented experiences because of the deep integration of the relevant devices with their bodies (except perhaps at a very high cost), then the grid (however short-lived, after so many decades of advancing individualization) of intersubjectivity will begin to unravel. What will be the empirical common ground on which these subjects can stand and establish channels of communication? How will they be able to converse and with what language as a vehicle? Will “the work of the translator” still be possible once the experiential community of feeling, that secret language of human creatures (and living beings in general) that animates individual human languages, has been drained?

The issue is obviously not only “communicative.” Since identity and self-perception emerge through intersubjectivity, as nodes on the node of social relations (an individual being could not even constitute an identity), any unraveling of this node would automatically mean an unraveling of individual identities. This would of course be an absolutely extreme scenario with little chance of realization. In the most extreme case, it would involve the possibility of even creating new biological species through such a process of continuous techno-biological differentiation. Even in the mildest scenarios, however, the problem of identity constitution remains. Individual and collective identities. The Fourth Industrial Revolution seems to envisage a universal disembodiment, not only in relation to work and the knowledge it requires, but also in relation to the basic functions of the body, even in relation to the self and its constitution as a totality. The self has, of course, never been an isolated unit, excluded from the rest of the world. Its submission to the norms of all kinds of devices and algorithms, however, is nothing less than annihilation.

In addition to the above, somewhat philosophical and existential issues, there is another one that is extremely political and economic. It is the question of the cost of social reproduction of subordinate strata in Western societies and the relation of this cost to the Internet of Bodies. What are the benefits of the Internet of Bodies, according to World Economic Forum estimates:13 “enable remote monitoring of patients,” “improve patient engagement and promote healthy lifestyles,” “advance preventive care and precision medicine,” and “improve workplace safety.” It does not take a particularly penetrating eye to realize that the main purpose of this whole campaign to quantify the body and make its information available to the outside world is to control it more closely, to monitor it so that its bad habits can be eradicated and the feeling that it does not belong to you as you thought, that any mistreatment of it constitutes anti-social behavior. Behind the chatter about precision medicine, preventive treatments and continuity of care lies a fundamental restructuring of the concept of health, health care delivery systems, the relevant rights that patients can demand and the corresponding obligations on the part of the state and private providers. The costs of social reproduction are now considered “unsustainable”-or, in other words, only seemingly contradictory to the “unsustainable” costs, the social reproduction sector of health can become extremely profitable if it is freed from the unnecessary “fat” of “I decide when I am sick, when to get treatment, and whether to follow the advice of this or that doctor.”

Perhaps it would not be an exaggeration to say that we are entering a model of lean social reproduction, a paraphrase of the term lean production (also known as toyotism). Disease, especially unauthorized disease, is now seen as waste, as something that must be anticipated and prevented. And when this is not possible, it should be eliminated as soon as possible under the watchful eye of the physician.14 It would be naive, however, to believe that this will at least result in an overall improvement in health. Just as toyotism was not introduced into the production process in an attempt to de-grow, but precisely to increase production, so too would health toyotism probably increase morbidity levels by being able to decide for itself what is morbid. The unfortunate thing: it will not be about the morbidity of individual diseases, but about morbidity as a constitutional condition of social existence, of society as a huge intensive care unit where all biological indicators will be recorded. Such a society in permanent conflict with its environment and surrounding nature is already a morbid society at its core. Its only escape will be painkillers, tranquilizers and self-destruction.

Separatrix, Cyborg Magazine, no. 23, Athens

https://www.sarajevomag.net/cyborg/cyborg.html

Published in L’Urlo della Terra, num.10, July 2022

Notes

1 – See previous related articles in Cyborg: “Many, too many, and healthy: health big data is another gold mine,” v. 18; “Wearable, portable, subcutaneous: the body as motherboard,” v. 10; “Precision medicine: the personalization of medicine,” v. 9 (in Greek).

2 – The term is not ours. See World Economic Forum article, “Shaping the Future of the Internet of Bodies: new challenges of technology governance,” July 2020, https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_IoB_briefing_paper_2020.pdf

3 – https://web.archive.org/web/20140121011604/http://

motherboard.vice.com/blog/googles-internet-of-things-now-includes-your-body

and https://www.vice.com/en/article/gvyqgm/the-internet-of-bodies-is-coming-and-you-could-get-hacked

4 – “The Internet of Bodies,” William & Mary Law Review, 2019.

5 – https://www.rand.org/about/nextgen/art-plus-data/giorgia-lupi/internet-of-bodies-our-connected-future.html

and https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3226.html

6 – https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/06/internet-of-bodies-covid19-recovery-governance-health-data/

7 – “Intelligent Ingestibles: Future of Internet of Bodies,” IEEE Internet Computing, 2020 (https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9195138), “The Internet of Bodies: A Systematic Survey on Propagation Characterization and Channel Modeling,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 2022 (https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9490369)

8 – Dick Cheney, the well-known former vice president of the United States, received one of these smart pacemakers. However, after some time it was decided to disable its Wi-Fi interfacing capabilities with the outside world for fear of possible hacking of the device.

9 – We reported on memory research in the previous issue, “The Engineering of the Spirit,” Cyborg, vol. 22. (in Greek)

10 – For disengaged constructivists, there should be no problem. Just to suggest that such infinite plasticity might have negative consequences is automatically to commit the error of “essentialism.” Blessed are the poor in spirit…

11 – To those who think this is a bit much, consider that it is already happening to some extent: through the separation into the vaccinated and the unvaccinated. The healthy body has essentially been outlawed. This separation is now also taking on clear class dimensions, with the middle and upper classes of the WAPL (white Anglo-Saxon progressive liberals) being overrepresented in the set of vaccination zealots and social disciplining measures. See the short article on unherd: “To witness the covid divide, walk from Brooklyn to Queens,” https://unherd.com/thepost/to-witness-the-covid-divide-walk-from-brooklyn-to-queens/. Fortunately, the vigilant left is not so easily seduced by the facts of reality and is holding firm. It calls for more vaccines for the whole world, even if the rest of the world does not want them. Some other “revolutionaries” on the other hand, having well assimilated the lessons of union maneuvers, insist that vaccination is a secondary issue (“we are against segregation, but anyone who does not vaccinate is an idiot”). Και την “επαναστατική” πίτα ολάκερη, και τον σκύλο της (διανοητικής και κοινωνικής) βολής χορτάτο. Greek folk proverb. The meaning of the proverb is that someone wants “all his meat” but also “his dog satiated.” Wanting all the “revolutionary” bread and, at the same time, their secure intellectual and social position… [ed.]

12 – No, we are not constructivists even at the level of language, we do not see it as a system of arbitrary conventions. Those who have not yet overcome these childhood illnesses should look at Benjamin’s writings. See: W. Benjamin (ed.), Essays on the Philosophy of Language.

13 – Shaping the Future of the Internet of Bodies: New challenges of technology governance, WEF, 2020, https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_IoB_briefing_paper_2020.pdf .

14 – This is not a fictitious scenario. An insurance company refused to cover the costs of apnea patients based on data sent by ventilators to its servers, without the patients’ knowledge. Patients who used the machines for less time than indicated in the instructions lost reimbursement. See, “Health Insurers Are Vacuuming up Details About You – and It Could Raise Your Rates,” ProPublica, 2018, https://www.propublica.org/article/health-insurers-are-vacuuming-up-details-about-you-and-it-could-raise-your-rates

Source: Resistenze al nanomondo