Source: La Nemesi

Émile Henry (Sept. 26, 1872 – May 21, 1894)

“Comrades, courage. Long live anarchy!” On May 21, 1894, the anarchist Émile Henry was guillotined. A few words for a comrade who dedicated his short and intense life, integrally and to the end, to anarchy. So many years have passed – well over a century of actions, dreams, revolutions – and the revolutionary will of this comrade continues to shine with the infinite wonderful facets of our ideal. Émile is immortal.

Aphorisms

Once, the cloister opened for souls weary or disgusted with the spectacles of the world, today we have no other refuge than in hospitals and prisons.

What do anarchists want? The autonomy of the individual, the development of his free initiative, which alone will be able to assure him all possible happiness. If the anarchist admits communism as a social conception, it is by simple deduction, because he understands that it is only in the happiness of all, free and autonomous as he is, that he will find his own happiness.

When a man, in today’s society, becomes a conscious rebel of his own action-and such was Ravachol-it is because he has done in his brain a painful work of analysis whose conclusions are imperative and cannot be evaded except by cowardice. He alone holds the scales, he alone is judge of the right or wrong of hating and being savage, “even fierce.”

I believe that acts of brutal revolt are right, because they wake up the masses, shake them like a violent lash, and show them the vulnerable side of the Bourgeoisie still all trembling at the moment when the Rebel goes up to the gallows.

Everyone has a special physiognomy and attitudes that differentiate him from his fellow fighters. Thus, we are not surprised to see revolutionaries so divided in the direction of their efforts. We wonder what good tactics are: they are everywhere proportional to the amount of energy brought to the action. But we recognize no one’s right to say, “Only our propaganda is the good one; outside of it there is no salvation.” It is an old residue of authoritarianism born of true or false reason that libertarians must not tolerate.

Do what you think is best and do it with love.

To those who say, “Hate does not breed love,” answer that it is love, alive, that often breeds hate.

Hate that rests not on low envy, but on a generous feeling, is a healthy and powerfully vital passion.

The more we love our dream of freedom, strength and beauty, the more we must hate that which opposes its future.

In the history of human progress there is only one party; it is the party of movement.

Socialists do not want to understand that the freedom of the individual is necessary to the true freedom of the people.

In the dedication of his book, From the Other Side, Alexandre Herzen specifies a truly revolutionary and effective attitude when he says, “We do not build, we demolish; we do not announce new revelations at all, we suppress the old lie.” This book by Herzen is full of flashes and revelations, but there is no lack of biting remarks in it either: it is a good book for the prison; and away from the street I like to take it as an echo: “The French cannot rid themselves of the idea of monarchical organization; they have a passion for police and authority; every Frenchman is in his soul a police commissioner; he loves alignment and discipline; everything that is independent, individual, irritates him; he understands equality only as leveling and willingly submits to the arbitrariness of the police as long as everyone submits to it. Put a chevron on a Frenchman’s hat and he becomes an oppressor, he begins to oppress anyone who does not wear that rank; he demands respect towards authority.”

There is one right that overrides all others; it is the right to insurrection.

The free man is the one in whose eyes philosophers are superstitious, and revolutionaries conservative.

Liberals are in politics of the same odious breed as Protestants.

Modern society is like an old ship that will sink in the storm for not wanting to get rid of its cargo accumulated during the voyage over the centuries; there are precious things in it, but they weigh too much.

All political parties are worn out, that’s why we appear.

The worker who gets drunk at least once a week does no different from the illusion-seeker. If I were a philosopher I would write something about the need to get drunk to numb the will that makes us suffer.

How many beings have gone through life without ever waking up! And how many others have realized that they were living only because of the monotonous tick-tock of clocks!

Between the bliss of unconsciousness and the misery of knowing, I have chosen.

So far peoples have understood brotherhood only as Cain and Abel did.

What about those revolutionaries who are only vile reasoners and who reflect when to strike instead? The sphere of general ideas has replaced the world of contemplation in them.

There is an assertion by Proudhon that, in his time, was considered immoral and would be criminal today. Namely, that the Republic is made for men and not individuals for the Republic.

Man sometimes needs to believe in the power of his own will; that is when he enters the struggle.

Between the economists of themselves and the prodigals of themselves, I think the prodigals are the better calculators.

The more we love freedom and equality, the more we must hate what opposes the freedom and equality of men. Thus, without losing ourselves in mysticism, let us place the problem on the ground of reality, and say: It is true that men are only the product of institutions; but these institutions are abstract things that exist only insofar as there are men of flesh and blood to represent them. There is therefore only one means of striking at institutions: striking at men.

A will that goes so far as to commit suicide can generate final and hopeless acts of dedication.

One of the first teachings of anarchy is this, “Develop your life in all directions, oppose to the fictitious wealth of capitalists, the real wealth of individuals possessing intelligence and energy.

I love all men in their humanity and for what they should be, but I despise them for what they are.

Moreover, I have well within my rights to leave the theater when the play becomes obnoxious to me, and even to slam the door on my way out, even at the risk of disturbing the tranquility of those who are pleased with it.

Grande Roquette, May 1894

[These “posthumous aphorisms” were first published under the title “Pensées” in “Le Libertarie” No. 28, May 23-29, 1896. They then appeared in No. 7 of “Documents d’histoire” (February 1907), which Fortuné Henry published in Aiglemont (Ardenne)]

[Excerpted from Émile Henry, Colpo su colpo, Edizioni Anarchismo, Trieste, 2013, pp. 137-142. First Italian edition: Émile Henry, Colpo su colpo, Casa Editrice Vulcano, Bergamo, 1978. The second edition (Edizioni Anarchismo) is also available online: https://www.edizionianarchismo.net/library/emile-henry-colpo-su-colpo]

Introductory note

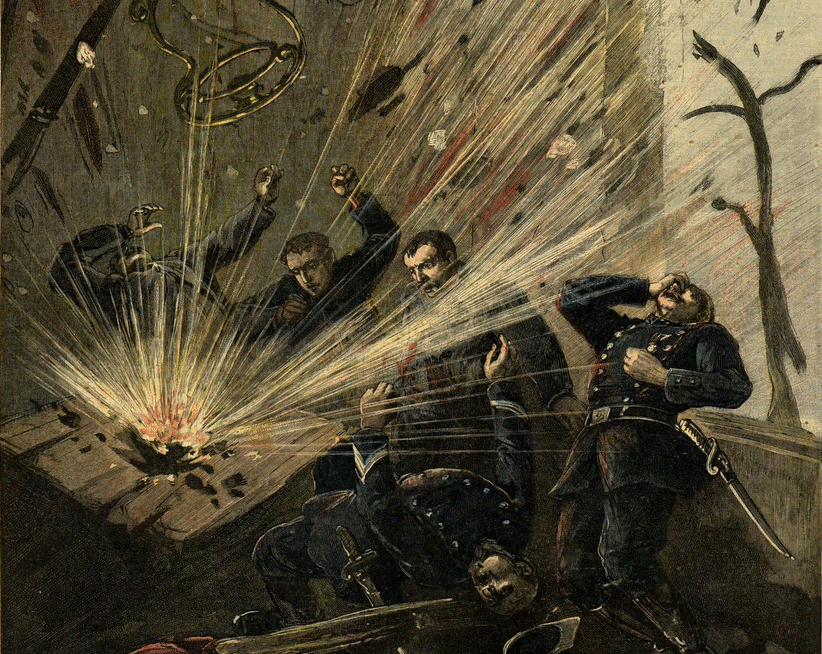

He who raises his hand against the rulers and their servants pays with his life. That is the lesson one draws from reading this book dedicated to the story of Émile Henry, the anarchist who decided in the late 19th century to attack the class enemy with bombs.

Let the comrades who delude themselves into thinking they are putting fear into them keep this in mind. Those who run the domain are not easily frightened. They close ranks and move on. Indeed, as soon as a few fires are lit here and there, they immediately call for special laws and exemplary measures. Normal administration.

It is up to us to decide what to do. Stand by and watch, waiting for everything to fall apart so we can get off the sidewalk we are standing on, or attack first. Even at the cost of finding lined up against-who could have imagined it-a good portion of our own comrades. Malatesta, in his time, others in our day.

This booklet, first published by Editrice Vulcano, in 1978, and immediately reviewed by me in ” Anarchismo ” gave rise to a far more rancorous and indigestible polemic than Malatesta’s soprano but, after all, generically good-natured lines (given here in the Appendix). Those who wish to read it will find it in my book: Gianfranco Bertoli and Alfredo M. Bonanno, Carteggio 1998-2000, Trieste 2003, pp. 450-480. Below I simply quote my review that gave rise to so much squalor. And I take up this writing of mine because I still consider it to be valid to clarify the reasons for Henry’s attack, which always remain the primary goal of every anarchist who wants to look at himself in the mirror in the morning without laughing in the face seeing reflected the mask of a buffoon.

So much for all philosophical distinctions.

Trieste, Oct. 30, 2011

Alfredo M. Bonanno

* * * * *

A collection containing a biography of Henry, two of his letters, an account of the trial, some aphorisms, and an appendix with an interesting letter from Malatesta.

The little volume, it must be said at once, presents a problem that far surpasses the foolish barbarism of historians, even historians of anarchism: Henry’s act was something frightening, something that shook not only so-called “public opinion,” but also his comrades. And Malatesta’s letter, included in the appendix, is an example of these perplexities, grasped by the Italian anarchist and justified in a certain way, putting forward the usual caution, the same caution that a few years earlier had made people like Grave and like Kropotkin cry “provocateur” against Ravachol.

But, let us go in order.

It is not at all true that Henry’s gesture fits into the chain of attacks and attacks that the “turn of the century” anarchists carried out against institutions and their representatives. Henry’s gesture operates a “quantum leap” that was grasped, albeit nebulously, even by comrades who were struggling against repression at the time.

This young man, educated and intelligent, coldly operates a decision that others had matured and understood, but not realized: he attacks the bourgeoisie, not this or that representative of the state institution, this or that policeman, magistrate, executioner, torturer, spy or traitor, no: the entire bourgeoisie. He strikes in the heap, without discrimination. He carefully chooses one of the places this class frequents, goes there with his infernal device, lights the fuse, throws the bomb and leaves.

More, he also tries to escape capture. He is not a martyr, he is a guerrilla, he does not want to sacrifice himself, he wants to continue in his struggle, he wants to continue to strike at the pile of shit. To do this he flees, he tries to cover his retreat, he shoots to defend himself, until he falls prisoner into the hands of the enemy. And here, once he is caught, he does not ask for mercy, he does not close himself in a muteness that is otherwise even justifiable: he makes the trial a tribune to explain and illustrate his deed against everyone (comrades included) and everything. He does not seek extenuating circumstances, he does not speak of “mistakes,” but he makes it clear that he intended to strike right into the heap, without prior discrimination, because right into the pile lurk those culprits of exploitation who are least identifiable, the representatives of that shopkeeping, respectable, cowardly, sanfedist class, ready to rush to the squares where they guillotine, ready to clap their hands at any Napoleonic by-product, ready to put their support under the feet of the dictator on duty.

Included in Henry’s gesture is an analysis of the concept of class. Not so much in his letters or in the trial debate itself, but in the very gesture itself. The collective behavior of the bourgeois class includes, in clearly delineated forms, as a class in power (or direct supporter of power) a class consciousness well adapted to the specific reactions of power relations (ideological and economic). The bourgeois class knows what it wants, and the bourgeois fringe knows it even better than the middle and upper bourgeoisie. And this self-consciousness also expresses it in pastime, in entertainment, in choosing a café, a restaurant, a brothel, a cruise, a vacation spot. The selection one makes in these places is not only determined by the price of products, services and what one needs to have with him to go there, but is determined by the very air one breathes there, by the atmosphere that has been created there “on purpose,” by the choice of trappings, trinkets, pictures, mirrors, glasses and carpeting. A proletarian-even today, with all the pollution that has been caused by prevailing consumerism-would rarely set foot in the Caffé Greco in Rome, and if by mistake he happened to be in it he would soon flee from it, not so much because he was frightened by the prices charged there, but because he was estranged from the atmosphere that was created there and felt as something solid, an atmosphere that only by superficial evaluation can be brought back to the need of capital to “sell.” Here we are not talking about those mass places where sacrifice is made to the “commodity” god, we are talking about other, more intimate and collected places, where sacrifice to the religion of the “commodity” is made in a more refined form, in a form accessible only to a few, in a form that operates an automatic selection and is matched – almost perfectly – by the adaptation of bourgeois class consciousness to the situation of the relations of force in play today.

Let it not be said that the historical situation at the end of the nineteenth century was different from the present, and that these places were far more precisely “isolated” then than they are today, precisely because the bourgeoisie still at the height of colonial exploitation felt confident and wanted to self-gratify even with brothels and cafes as well as churches and victory monuments. Even today, undergoing profound social transformations, the bourgeoisie retains a certain self-consciousness, at least those sections that have not been sucked irretrievably into the abyss of criminalization as a result of the difficulties for capital to maintain a sufficiently secure level of employment. But those other bands, the guaranteed ones, the ones that have also swelled with the entry of other – previously proletarian – groups, today are the most coherent and hardest reactionary core to dislodge. And this core, this patchwork of interests and squalor, of slang language and cloying imitations of past splendor, this core is still to be found in the same places, the same cafes, the same brothels.

That’s it. What is most humorous (and tragic, at the same time) is that this reactionary core has taken on the attitudes of the wordy progressivism of the so-called left, and in order to better solidify the consciousness of its own social status has rejected the outdated robes of a reaction that wore black (and would make people laugh today) to put on the robes of a reaction that wears red and no longer makes people laugh but scares them.

Here. Hitting the pile today, so long after Henry’s gesture, would not only be a valid gesture but would also be a theoretical contribution to the movement, again, a qualitative leap.

Malatesta wrote, “It is one thing to understand and forgive, another to vindicate. These are not acts we can accept, encourage, imitate. We must be resolute and energetic, but we must try never to go beyond the limit marked by necessity. We must be like the surgeon who cuts when necessary, but avoids inflicting unnecessary suffering: in a word, we must be inspired by the feeling of the love of men, of all men.”

Love or hate. The alternative is wrong. In the class clash one cannot feel love for one’s enemy, the feelings that can stimulate this love are those of common reaction to the same class stimuli, that is, feeling not only a part of the same class as the enemy but feeling interested in the same things and ideals, otherwise, when the enemy sees himself as such – as a class enemy – and his interests and ideals are not shared, but rather arouse disgust and disdain, the result can be only one: hatred.

And Henry replied, “It is true that men are but the product of institutions; but these institutions are abstract things that exist only as long as there are men of flesh and blood to represent them. There is therefore but one way to strike at institutions; that is to strike at men; and we welcome with happiness all energetic acts of revolt against bourgeois society, because we do not lose sight of the fact that the Revolution will be but the resultant of all these particular Revolts.”

[Review of E. Henry, Colpo su colpo, Edizioni Vulcano, Bergamo 1978, pages 174, published in ” Anarchismo ” No. 23-24, 1978]

[Excerpted from Émile Henry, Colpo su colpo, Edizioni Anarchismo, Trieste, 2013, pp. 5-11. First Italian edition: Émile Henry, Colpo su colpo, Casa Editrice Vulcano, Bergamo, 1978. The second edition (Edizioni Anarchismo) is also available online: https://www.edizionianarchismo.net/library/emile-henry-colpo-su-colpo]