Fanzine and review of the documentary on CLODO (Committee for the Liquidation or Destruction of Computers)

A documentary delves into the mystery surrounding a group of anonymous activists who carried out a series of arson attacks in Toulouse in the 1980s.

In the 1980s, the French city of Toulouse was home to a number of companies that used computers to further the aims of France’s police and military-industrial complex. These companies, such as Sperry Univac – a major U.S. equipment and electronics company – were among the first to create digital surveillance systems and manufactured products that would make warfare easier for the state by improving the accuracy of missiles.

In addition to housing these private military companies, Toulouse was also home to a milieu of radicals, including Spanish anti-fascists fleeing Franco; Action Directe guerrillas; and a new left forged in the aftershocks of May 1968, when students and workers staged a series of strikes that rejected the authority of the ruling Gaullist party and the orthodox Marxism of the French Communist Party.

It was in this context that an activist group called the Committee for the Liquidation Or Destruction of Computers (CLODO) emerged, which carried out several arson attacks against computers of military technology companies in Toulouse during the 1980s. Not much is known about CLODO. It disappeared completely after committing some six successful and two unsuccessful attacks against technology companies, leaving satirical communiqués as the only proof of its existence.

An introduction to the translation of one of its communiqués suggests that the group may have emerged from a citywide coalition to prevent the construction of the Golfech nuclear plant on the local Garonne River. In 1981, when this movement reached a stalemate, some participants resorted to an intensive campaign of sabotage. CLODO, who claimed to be computer workers, may have taken this sabotage impulse and applied it to computers, which in their view were “the preferred tool of the rulers. They are used to exploit, file, control and repress”.While other left-wing radical groups of the time, such as the Red Brigades or Action Directe, were extremely serious, committing assassinations and writing dense anti-imperialist treatises, CLODO operated in a more playful manner. After their actions (which never hurt anyone), they left humorous graffiti and satirical documents, such as the “self-interview” they sent to Terminal magazine. In the interview, they answer their own questions with biting insults, suggesting that their fellow computer scientists ” rarely use their gray matter “, and provocations, such as asking ” what could be more ordinary than throwing a match on a pack of magnetic tapes? “. Even his name was a joke; CLODO in slang means something like bum.

But it was never clear who the pranksters were. In a 2022 documentary, Machines in Flames, filmmakers Thomas Dekeyser and Andrew Culp investigate CLODO and the mystery surrounding it. Culp and Dekeyser use unconventional techniques-such as allowing part of the narrative to unfold on the screen of a Macbook-that stay true to the group’s anarchic spirit.

Dekeyser first came across CLODO in an old computer engineering textbook and began researching them. He soon realized that there was very little information beyond self-published releases and mentions in the press of attacks on Phillips Data Systems, CII Honeywell Bull and Sperry Univac companies.

“[Culp and I] were immediately drawn to this group,” says Dekeyser, ” not only because there was so little information (although that added to the mystery about them), but also because of the way they stood out from other groups of the 1970s and early 1980s; their playfulness, the fact that they were never caught and that they themselves claimed to be computer workers. All these little elements added up to become a kind of obsession”.

CLODO were not primitivists like Unabomber or the contemporary ITS group from Mexico, who want to return to a pre-industrial state of society. According to Dekeyser, CLODO was not against all technology, but attacked computers because they saw “computing, especially in the hands of the military or the police, as a way of reducing chance and nullifying the possibility of revolution.” Nor were they Luddites because “they were not concerned about working conditions.”

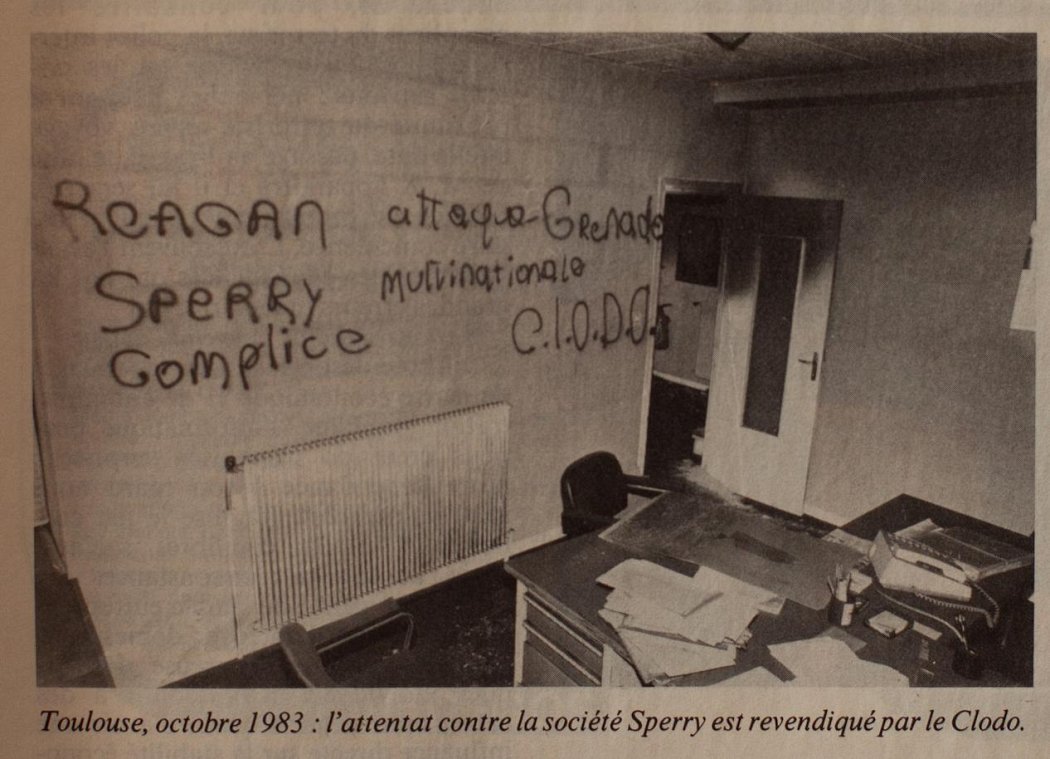

A day after President Reagan ordered the invasion of the Caribbean nation of Grenada, CLODO attacked the offices of Sperry Univac in Toulouse, setting fire to its computers and writing on the wall “Reagan attacks Grenada, Sperry is a complicit multinational”. According to Dekeyser, this shows that CLODO maintained a connection with the ultra-left environment from which it emerged. “The attack on Sperry places CLODO in a long line of anti-imperialist struggle in continental Europe at the time, which considered as one of its central objectives to find the structural weaknesses of global imperialist capitalism,” he says.

The attack on Sperry was revenge for Grenada. “When corporations initiate these forms of violence there is always going to be a response,” says Dekeyser. “CLODO was just closing the circuit of violence. In the logic of anti-imperialism, Sperry Univac had brought it on itself.”

Although these actions garnered widespread attention, “CLODO covered its tracks,” Dekeyser adds. “They wrote very proud of their own anonymity and how they knew more about the state than the state knew about them. He says that soon enough, he and Culp began to realize that, in compiling all this new information about CLODO, they were partly replicating what the police probably did to track down the group. But instead of trying to unmask them, the project stays true to the logic of CLODO. The filmmakers are designing USB sticks that contain the film and temporarily disable the computers they connect to. They intend to distribute them to corporate campuses of technology companies and project the film on the sides of their buildings.

Although relatively unknown and active for only three years, CLODO has had a strange afterlife. Dekeyser gives the example of a group tried in the early 2000s for attacking high-speed rail power lines in an action that was reminiscent of CLODO and likely inspired by it. Although no one was found guilty, it is believed that behind it were people from the Invisible Committee, an ‘ultra-left’ cell whose manifesto included a passage about attacking HST power lines in the face of slowing down the speed at which society operates and preventing people from being forced to commute to work.

The film also hints at the possibility of a modern CLODO. In 2017, a ” fablab ” – a laboratory that manufactures products combining computer-aided design and 3D printing – was set on fire in Grenoble by an anonymous ultra-left group described by the police as ” anarcho-libertarians “. In their communiqué [1], the group described Case-Mate and the lab’s owners as ” a notoriously harmful institution ” for the way they used computers to interact with processes that had hitherto remained offline, such as construction and design. They also wrote that society was falling prey to a “technological totalitarianism”. CLODO may have disappeared in the 1980s, but its spirit – fighting a society dominated by networked technologies with fire as a weapon – lives on.

Dekeyser says it’s possible that CLODO was in its 20s and 30s when it committed its attacks, so its members are likely still around to witness the current era of technological saturation. ” I’m pretty sure they’re not happy with the way things are, ” he says. ” But they also would have known from the beginning that this is where we would end up.”

Links of interest :

Fanzine [ES]: ¿Has oído hablar de CLODO?

Fanzine [EN]: Memory Loss. Collected communique from CLODO

Web of the documentary ” Machines in Flames ” https://machinesinflames.com/0

—

Note

[1] Communiqué of the attack on Casemate, 2017.

Grenoble, a pacified technopolis?

The night of November 21 we have entered Casermate in Grenoble (easier than expected as the door was open (idiots!)). We smashed it up (anyone who has ever thrown a computer out of a window knows what we are talking about) and then cheerfully set fire to it. While the telegenic responsible for this fablab appears pathetically in the media, we publish this communiqué, an inseparable echo of our incendiary gesture against this institution notorious for its diffusion of digital culture.

In the 1970s, many revolutionaries invested in the Internet when the computerization of our lives was still in its infancy. There was frantic talk of horizontality, of the wonderful potential for information and information sharing, and even, for the more clueless, of emancipation through connected computers. Popular appropriation of this emerging technology would, it was claimed, undermine all coercive attempts by governments or commercial enterprises. Over the course of half a century, this naïve utopia was transformed from a fringe prophecy to a popular ideology. From government leaders to left-wing intellectuals, from cyber-entrepreneurs to environmental associations, all are fascinated by the digital revolution. The hacker has become the new subversive icon, and social networks, open source, collaborative work, transparency, free access and immeasurable immateriality are praised everywhere.

But overcoming the industrial age has turned out to be a big lie: thousands of kilometers of cables under the earth and the sea, data centers in every corner of the hemisphere, a whole regiment of nuclear power plants to sustain the economy, sophisticated products with accelerated obsolescence, screens everywhere, noxiousness even in the most intimate of our daily lives; everything is based on hypertrophied industry, the destruction of the last undeveloped environments and the brutal or diffuse exploitation and elimination of individuals human or not.

The digital lure continues to have an effect. However, the inimitable Norbert Wiener theorized cybernetics as the art of governing by machines as early as 1954. Yet it was the world’s greatest military power that developed the first computers and networked them for the sole purpose of effectively winning the war. However, it is Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, who program the web and get rich from it. However, it is the States that regulate and police the digital space. Undoubtedly, profit and control preside over this immaterial fantasy. Society ends up being reduced to a finely modeled technological totalitarianism, an increasingly authoritarian version of our lives. What do revolutionaries do? They co-manage their own alienation, create digital currencies and install wifis even in squats.

When everything contributes, in lived reality, to deny ideology, ideologues redouble their inventiveness. Communication and images must disguise the world to safeguard the reign of the false.

” Ville Internet ” [contest for the best internet coverage as a public service – ndt] now joins ” Vile Fleurie ” [contest for the best green space – ndt], all the latest technological gadgets are ” smart “, bureaucrats in the national education system hand out digital folders to children. New and entertaining digital interfaces are being introduced everywhere. City administrations cater to money-hungry start-ups and the geek masses by opening fatlabs in trendy neighborhoods. All these seemingly totally heterogeneous devices are intended to accelerate the social acceptance and use of the technologies of our sinister age.

And we don’t give a damn if these fablabs are the product of the imagination of an admired hacker -this is not the case- or if they are part of fruitful scientific collaborations in one of the temples of technocracy, the MIT (Massassuchets Institute of Technologies) -this is the case- ; precisely because they represent a noxiousness we have come to destroy one. But it is not a question of criticizing this or that aspect of technological hell, of deploring the progress of the omniscience of the State, the efficiency of the market order or our increasing domestication by the machine. If we fight against the cybernetic project that accepts our submission, we are attacking the totality of this abject world.

We are a little late for the date of the 16th (trial) but we send our support to the compas in the Scripta Manent operation (especially to those who suffer censorship). We also send strength to the three compas from Montreuil who are currently in custody and to the comrade in solitary confinement.

Compas from Chile have launched a call for a Black November. Although we like the idea of an international campaign in support of anarchists, we do not agree with the idea of “the demand to free the prisoners”. Even if we share the idea of supporting the rebel prisoners with attacks, we refuse to enter into a logic of dialogue with the State (or with any power).

Tonight we have burned Casemate, tomorrow it will be something else and our lives will be too short, in prison or in the open air, for all that we hate to be consumed.

Source: Contra Toda Nocividad