The Internet of bodies: the body as a technological platform

Introduction

It has not even been ten years since the Internet of Things made headlines and fueled the dreams of technologists around the world. Smart clothes that can measure your mood and update your cell phone, smart glasses with which you can overlay reality with a second layer of your own, e.g., with personalized realities, smart and inexpensive light bulbs charged with carrying the burden of your eco-consciousness by turning on only when you are in the room or when you give the command from the controller of your life aka smartphone, smart coffee makers, ingenious mugs, wi-fi-enabled sinks, and the list goes on. All this new “smart” and illusory life promised by the universal interconnection of everything on the Internet has turned out to be, at least so far, a mere fantasy. But is this proof of the failure of the Internet of Things? In a sense, the answer should be yes (again, at least for now), at least if one is to take such promises at face value. On the other hand, the Internet of Things can be considered as much of a “failure” as any new model of an automobile-based society is a “failure” because its drivers end up spending most of their time moving at the pace of a sloth on Alexandra rather than with feline grace on open roads, vast expanses of open country, or meandering, scenic roads perched on green mountains, as they should, given the commercials. The crucial difference in the case of the Internet of Things, which will provide the measure of any failure or success, is that it was not simply an attempt to promote a product or even a range of products. What was widely promoted or even mandated was not so much and not only the lures of smart devices, but the very idea of universal connectivity, the notion that information can be drawn from anything and that this information can be valued, exploited and enhanced.

There have been many, too many, probably the vast majority of individuals in Western societies, who have seemed all too willing to take the bait of all kinds of smart devices. Finding themselves with the hook of universal interconnectivity stuck in them, perhaps not yet sufficiently aware of the consequences of the position they have found themselves in. The oceans of psycho-intellectual novocaine in which they swim daily (courtesy of social media and subscription lobotomy platforms) do not leave them much room to maneuver. The extent of this retreat of conscience and panicked concession of battlefield positions that would once have been considered non-negotiable has become evident, if nothing else, with the recent issuance of health certificates. The docile readiness with which the subjects display the symbols of their unworthy conformity to a paranoid regime (even for unnecessary movements, such as those related to work or studies) is a low point but not the nadir of political and aesthetic-moral decline; at the other end of the sewer are those who assume the role of controllers, not infrequently enjoying their role, even if they do not openly admit it, perhaps not even to themselves (their tone of voice and body language are, however, irrefutable witnesses). A marvelous social condition that allows microclimates and alveolus to be created everywhere, within which the mushrooms of petty authoritarian attitudes acquire the status of the self-evident: the teacher checks the pupils (a mischievous person might say, “this is not a new role for teachers”), the clerk checks the teacher when he shows up as a customer, the waiter checks the clerk when he goes to buy coffee, etc. Everyone is given the opportunity to assume the role of the examiner; but no one is spared the role of the examined: in other words, the definition of the cannibal condition.

A nontrivial reminder: all these things owe their “success” in large part to the fact that they are mechanically mediated. The smartphones that promised the blossoming of a life in which everything would be available at (or even before) the push of a button seem to have first spread the manure of social barbarism in the form of mutual surveillance. It is obvious that without the ability to instantly scan and identify a certificate, the entire “medical” surveillance regime would be unstable and to such an extent that it might eventually collapse. But who would dare to oppose such practices among those who, for the sake of any free “convenience,” have become spineless data bleeders through their interconnected devices of all kinds? Continue reading “The Internet of bodies: the body as a technological platform” →

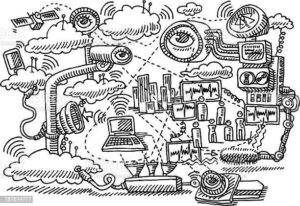

other, depending on the location. One only has to look around to see the continuous installation of new repeaters, or the continuous installation of new antennas on existing ones. What few people know is that there will be many ‘mini-antennas’, camouflaged both in street furniture (lampposts, manhole covers, bus stops, etc.) and in everyday objects, not to mention the thousands of satellites that have been launched, and will continue to be launched, into space, to connect even the most remote places on earth. What is known to date about the network already in use is that it causes serious and irreversible damage genetically, biologically and to the reproductive system, which makes it clear that its enhancement (by means of the installations we have just discussed) will cause even greater damage to all living things, further aggravating a situation which already today appears dramatic.

other, depending on the location. One only has to look around to see the continuous installation of new repeaters, or the continuous installation of new antennas on existing ones. What few people know is that there will be many ‘mini-antennas’, camouflaged both in street furniture (lampposts, manhole covers, bus stops, etc.) and in everyday objects, not to mention the thousands of satellites that have been launched, and will continue to be launched, into space, to connect even the most remote places on earth. What is known to date about the network already in use is that it causes serious and irreversible damage genetically, biologically and to the reproductive system, which makes it clear that its enhancement (by means of the installations we have just discussed) will cause even greater damage to all living things, further aggravating a situation which already today appears dramatic.